The Danish-Greenlandic Environmental Cooperation

Hunters and scientists

Who should control hunting? What does sustainability mean with respect to reindeer, belugas or thick-billed murres? How are conflicts over the environment to be handled? Part of Dancea's environmental program supports activities that help solve local environmental problems.

"I get so furious when people say there's no debate on the environment in Greenland. If they debate anything here, they debate that. All the time. It is just that they don't discuss environmental questions the way politicians want them to," snorts Frank Sejersen, an eskimologist at the University of Copenhagen.

"I work with sustainability in general," says Frank Sejersen a bit more calmly, and continues, "Everyone uses the word sustainability, but they mean different things by it. I am trying to sketch out these different perspectives on sustainability. To show the differences, and to show why people talk past each other when we discuss sustainability and think we are all talking about the same thing."

Frank Sejersen is a scientist. And scientists are always in doubt. Are, on principle, never entirely sure.

"I have spent a lot of time in Sisimiut, because it is a place where the conflicts are very visible," says Frank Sejersen, "and that's just because there are so many different interest groups represented."

Let us take a concrete example like beluga hunting. Every one in Greenland is allowed to hunt beluga. That means that when you go on a beluga hunt, you'll meet the mayor, you'll meet a millionaire, you'll meet a hunter, and you'll meet a recreational hunter. Everyone. But they all have different reasons for needing this beluga. Some feel it is a right, that it is a question of cultural values. For others, it is simply something they enjoy doing. Still others say, "If I don't get this beluga, I won't be able to pay my bills." That is why so many conflicts arise on a beluga hunt. Who should get how much of the beluga?

It almost sounds like both fights and court cases could take place across the back of the whale.

"There has been the threat of fighting, and there's actually a recreational hunter who took a group of professional hunters to court because he thought he was not given his fair share," says Frank Sejersen.

The discussions take place on a local level. Frank Sejersen sees this as an advantage, because then the people themselves are in control. Another advantage is that there is a continuing debate. Fixed rules would trap people in categories. Flexibility would be lost.

Several hunting companies have been active in East Greenland. This is a hunting cabin in Kap Biot, Jameson Land. A polar bear has ripped the door off.

But, I ask, could that not cause the hunter who actually does live off hunting to be stepped on?

"It sure could," he answers, "but it could also mean the opposite. Who should have a right to the whales?" asks Frank Sejersen rhetorically.

Control over hunting

Hunters are organized in different ways. There are the local hunting and fishing associations (KNAPP), there is the umbrella hunting and fishing association (KNAPK), which takes care of negotiations with politicians, and there is the new organization of recreational hunters. The Home Rule Government is very interested in working with the hunters. It is not surprising when a central organization tries to collaborate with local representatives. But - as Frank Sejersen points out - they could also do the opposite, and delegate the responsibility to the local councils. The Home Rule Government could very well say "You can shoot 200 reindeer, but decide for yourselves how you will share them. In return, you also have to help monitor the population." And the system does not have to be the same from one local community to the other. That could easily turn out to be biologically and socially sustainable, but the question is whether the Home Rule Government will regard it as "politically" sustainable.

In short, the government - in this case, Home Rule - has its own ideas and assumptions about what is sustainable. Biologists have theirs. The local hunters still their own ideas and assumptions about how the hunt should proceed and be administered.

"My task," says Frank Sejersen, "is to sketch out the different strategies for sustainability."

The Home Rule Government is evidently very reluctant to set bans or quotas. That is what happened with the thick-billed murre, the reindeer, the fin whale, and the minke whale. In times of crisis, when hunters are hard-pressed economically, those controversies flare up again. In Sisimiut, one of the dividing lines goes between recreational and economic interests. The recurrent question is, therefore: What is socially just?

Tourist interests are a new aspect. Tourists could hire hunters. Go hunting with them, and then get a share of the kill. It must present new economic possibilities.

"I don't believe that," says Frank Sejersen flatly. "There are only a few hunters (outfitters) that could handle that. It actually requires quite a lot. Big investments. Training courses. Now that the purchasing power of the hunters is getting worse and worse, many people are setting their hopes on tourism as the business of the future. They imagine that it must be a good alternative to hunting. It goes along with our idea that hunters can take tourists out with them and act as local guides. But a simple thing like taking a tourist out on a boat, that's forbidden. To take a tourist out, you must have a certain amount of safety equipment. It is expensive and the boat becomes so heavy that it can't sail. Besides, there are probably only a few people who can speak the languages that the tourists require. And when you have paid for your trip, you want to be sure that the guide will be there when you arrive. It won't do any good if your nature guide has just gone hunting. It would require completely different priorities in daily life."

Frank Sejersen thinks picturing hunters as the new nature guides for eco-tourism is pure fantasy, and an alternative for very few during the short season.

ResourcesHunters talk about economic and social sustainability, while biologists talk about ecological sustainability. In principle, biologists are indifferent to who kills the whales. It is not their decision. They are interested in deciding what is justifiable, what is necessary, and what is fair. All conservation hurts, and that is probably why the Home Rule Government hesitates in many cases.

With beluga hunting, the idea so far is that all Greenlanders should be able to go whaling. At the moment, however, when there are so many problems, the professional hunter thinks it is unreasonable that his neighbour, who is a millionaire, can go out and get the same amount of beluga as he himself can.

The Home Rule Government has, for example, forbidden shooting whales from trawlers. Put simply, it means that trawler owners are told: Concentrate on what you are good at, fishing shrimp. That is where you get your income. Let others utilize the belugas.

Traditionally, hunters migrated after their game, either to summer hunting grounds or to completely new areas. It was a question of the family's survival, not of protecting the animals. Traditionally it was not a question of ecological sustainability.

Sustainability is a modern concept, which is based on certain basic ideas: 1. There are certain populations. 2. You must control your behavior so that you do not overexploit the population, and you must monitor the number of individuals in the population. 3. You are administering a resource.

The word resource itself is part of the modern perspective.

In the past, animals were seen as human-like beings that were reincarnated after you shot them. If he respected them properly, the souls of the animals returned to the hunter year after year in the form of new animals. You might say that an animal with a soul is a woolly idea. But so is a population. Have you, for example, seen a population recently?

Nevertheless, you cannot claim that hunting is sustainable just because it is done in the same way as in old times. That would not contribute to the debate about what sustainability is. It would show a lack of respect for both traditional and modern societies.

In the old hunting communities there was periodic starvation. We would not tolerate that nowadays. Secondly, the human population has multiplied. And we would not accept the necessity of moving because of game.

"It is a strength of democracy that initiatives can come from all sides," concludes Frank Sejersen. "It might be KNAPK (the hunting association), it might be local activists, it might be the Home Rule Government. If the topic is quotas, for example, it doesn't matter who starts the discussion. Before last year, no one mentioned quotas for belugas except biologists and people in nature management. But the administration of quotas, how to solve conflicts - there could be many ways of figuring them out! Why not be open to that?"

Debate and education

Frank Sejersen's research is paid in full by Dancea. Part of his research involves outlining the perspectives of different groups on sustainability - biologists, hunters, politicians, and so on. He points out that sustainability is a modern, forward-looking concept. That is why he thinks that it is important to map out people's visions of how the country should be used and protected.

He also works with the question of how biologists can incorporate local knowledge into their work.

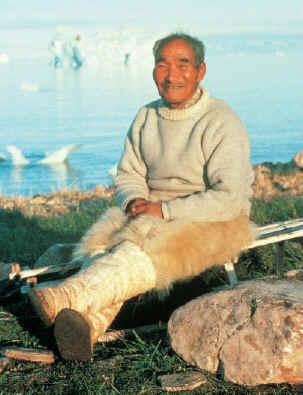

Imina Imina, photographed at midnight in Siorapaluk, 1975. At that time he was 77 years old. He lived near Kap York as a boy and could remember Knud Rasmussen's arrival there by sled from the south on "The Literary Greenlandic Expedition."

Finally, he is writing a debate book on natural resource management in Greenland, and hopes to draw parallels to other communities, especially other Inuit communities.

Frank Sejersen remarks that the point on the Danish Environmental Protection Agency's program dealing with increasing environmental awareness in the Arctic could be perceived as an attempt by external powers to administer the use of nature in Greenland. At the same time, a growing number of Greenlanders want more discussion of the environment, and want environmental education for Greenlandic youth, who, like youth in other parts of the world, are becoming increasingly alienated from nature.