The Danish-Greenlandic Environmental Cooperation

The dirty dozenThe most persistent pollutants are mainly produced and used in the industrialized parts of the world, but they reappear in concentrated form in the Arctic - in the air, and in plants and animals, both on land and in the sea. The first major comprehensive presentation of the state of the environment in the Arctic has just come out.

It is an impressive work. Thick as a telephone book. Eight hundred and fiftynine pages with chapters surveying the Arctic environment, drawn up in strict accordance with scientific method. On the accumulation of heavy metals. On the long journey that industrial and agricultural sprays make from southerly latitudes to the regions near the poles. On radioactivity in the Arctic environment. On how substances are interchanged among the living organisms on this shared planet of ours.

It started in Rovaniemi in 1991, when the eight countries that share the Arctic regions decided to start a common undertaking to measure and record the state of the environment in the Arctic: the AMAP project, which stands for the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program.

The resultant Arctic Assessment Report came out in the summer of 1998, and is the largest and most in-depth comprehensive status report on the state of the Arctic environment ever made. Dancea financed the Danish contribution to this project.

Old acquaintances

Once you have been out in the sometimes unimaginably beautiful Greenlandic landscape, which Greenlanders and we visitors cannot help falling in love with, it is almost unbearable to read about the many pollutants that are stealing into what used to be pure and unspoiled nature.

One of the cornerstones of the report is a chapter on the persistant organic compounds that are used in industry and agriculture, mostly in the Western world, and which accumulate in the Arctic food chains. They are called POPs, which is short for "Persistent Organic Pollutants". The worst of them are known as "The Dirty Dozen" and include the all too familiar substances DDT, PCB, chlordane, dieldrin, and others. Substances that are produced, for example, to kill insects or other pests in agriculture, but which have gradually been found guilty of other types of environmental damage, even in the Arctic.

The principle of accumulation in Arctic food chains is well known. What we do not know is how to stop the spread.

In order to describe the dissemination of POPs, how they develop over time, and their effects, we need to choose some animals that can be studied all over the Arctic. Key species. Since most of the food in the Arctic comes from the sea, AMAP has chosen the ringed seal as one of its key species. This seal is very common in the Arctic. It is hunted for its meat and pelt, and is an important food for the Arctic population. This makes it possible, by way of hunting, to get a large number of samples from the chosen monitoring areas to analyze, for example, for POPs.

Literature on the ringed seal describes it as fairly stationary. "But you should be wary of drawing hasty conclusions," says senior researcher Rune Dietz, who has researched the ringed seal and other Arctic animals for most of twenty years. "Satellite trackings have shown that the ringed seal does migrate around a bit. There is contact between Canada and Greenland. Seals that are, for example, marked in Qaanaaq (Thule), have been traced by satellite in Canada, and others have been found in Disko Bay. The ones that migrate are quite often young seals, so they are not as representative for a chosen area as the older seals. The older seals are more stationary, and only the wily ones escape hunters, nets and a number of other dangers."

Seal meat is used in hunting regions to feed both humans and dogs.

Ringed seals eat both crustaceans and fish, which have different concentrations of POPs and heavy metals. The proportions of these different groups of animal vary in different areas. "That is why food choice is a source of error, when you are evaluating the geographical or chronological development of POPs and heavy metals," says Rune Dietz.

The same in sumThe most important point in the evaluation of the development of POPs in recent years is their persistence. That is to say, it takes an extremely long time for them to break down into harmless substances. If we look, for example, at the well known spray DDT, it breaks down to DDE and then to DDD. These degradation products are also harmful; they are also among the POPs. A study of marine mammals, from 1982 to 1996, revealed that the concentration of DDT in beluga blubber had fallen, but that the concentration of the degradation product DDE had risen accordingly, so that the sum of DDT and DDE was the same through out the period of study.

The same was true for PCB and its degradation products, while a third member of the dirty dozen, chlordane increased significantly.

The AMAP´s The Arctic Assessment Report also maps out dispersal pathways. It describes how concentrations vary across the Arctic regions. It attempts to illustrate the development over time, as well as the biological effects on plants and animals.

POPs are measured on land, in the sea, and in the air. Air samples are continuously being analyzed from Svalbard in Norway, Ellesmere Island in Canada, the Yukon in Alaska, and the Lena River in Siberia. HCH, a substance that is used as an insecticide in the cotton industry, is being studied in the Mackenzie River in Canada, in three Norwegian rivers, and in the Ob and the Yenisey in Siberia. All the studies indicate that the chlorine-containing environmental poisons come from former and current use of POPs in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, and that these substances are transported to the Arctic by sea currents and winds.

Seal meat is a major part of the diet in some parts of Greenland.

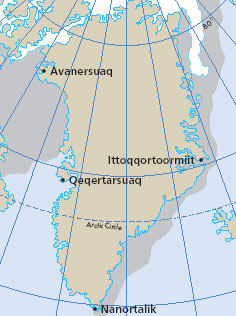

Worst in East GreenlandA study of land animals, plants, birds and marine mammals from Alaska and Canada in the west, to East Greenland and Svalbard in the east, would reveal a clear increase in of PCB, DDT, and HCH concentrations from west to east. In Ittoqqortoormiit (Scoresbysund) in East Greenland, ringed seals have higher concentrations of PCB and DDT than ringed seals in West Greenland do. The highest concentration ever was found in the Yenisey, a Siberian river.

The same is true of polar bears. The concentration of PCB in polar bears is significantly higher in East Greenland and Svalbard than in other places in the Arctic.

While heavy metals each follow a path through the food chain, and have certain organs they tend to accumulate in, POPs attach themselves to fat. To begin with, POPs can be grouped together and regarded as a whole. Different organs have different fat contents. When this is taken into account, roughly the same concentration levels are found in the different organs.

"POP concentration levels in ringed seals are not far from the threshold limiting value, but they are nothing compared to the concentrations found in seals in the Baltic, where they can be ten to a hundred times worse," says Rune Dietz, and continues, "Still, it is a problem in the Arctic, because seals are such an important part of the diet in Arctic Canada and parts of Greenland. It is not a problem for the inhabitants of Svalbard and northern Russia, because the ringed seal does not dominate their diet."

Polar bears, which eat only the fat of the ringed seals, get big doses of POPs. In polar bears, concentrations are perhaps twenty times higher than in seals. Studies done in Svalbard have shown that the immune systems of the polar bears are under pressure. The higher the PCB concentrations are, the greater the strain on the immune system.

For investigating direct physical damage, the bears would probably be more interesting to study than ringed seals, but scientific interest alone cannot justify going out and shooting twenty-five polar bears in different areas.

With respect to the effects of POPs on ringed seals, Rune Dietz says, "We haven't found any hermaphrodites among the ringed seals. If we want to look for conspicuous changes, we have to go one link up on the food chain, and study whether there are any effects on humans and polar bears." That is why a study of polar bears has been started. Hunters in Ittoqqortoormiit (Scoresbysund) are being paid to take samples from a hundred bears in all. These samples have almost all been collected. They will be studied closely during the next couple of years.

The daily doseThe internationally set threshold limiting values for substances injurious to the environment are one thing. How the concentrations vary over time is another. The limiting values are not so important as long as concentrations are declining. And conversely, if the concentrations rise continuously, then any threshold limiting value will be exceeded. It is only a question of time.

It is difficult to draw any conclusions from the results of the Arctic Assessment Report. The Swedish time trends are the best. They showed some pronounced drops in POPs during the 1970s, followed by a lessening decline.

In the Arctic, there are some places where concentrations have fallen over time, and other places where no conclusions can be drawn. In a few places, concentrations are actually rising.

Meanwhile, there are many intermediate calculations to be made. The males accumulate POPs throughout their lives. The females are different. A female will build up a certain concentration level in her body through her life. But when a female has her first-born, it will get a huge dose, while the mother's POP concentration level will decrease as she produces the high-fat mother's milk. Some female whales breast-feed their young for 11/2 - 2 years.

According to the magazine New Scientist, a Greenland whale has been studied and found to be 212 years old. This recordholding animal was born before the French Revolution! That means that these animals have been accumulating environmental poisons through out the period in which they have been produced. At the same time, these animals have only lived to be this old because they are extremely cunning, and must, therefore, contain a valuable gene pool. The Greenland whale has been protected since the 1930s, and has not recovered yet.

The problem, at the moment, is that it would take about seven or eight years, perhaps longer, of collecting samples to be able to conclude anything about the development over time. Expecting scientists to give a reasonable answer now on where things are going with respect to pollution concentrations in Greenland is like trying to predict how the national team will do in its next soccer match. New players keep appearing. Some are replaced during the game. And, most importantly, the opponent is not passive.

The same is true of the interplay between nature and pollution: nature is not a passive sparring partner. The data from Canada is a bit better. But even in Canada the time trends are not clear. Five years is a long time from a purely political point of view (though not for a Greenland whale). In a scientific context, longer periods are often necessary. This is especially true of time trends for POPs. An event of global significance took place in Stockholm in May 2001. The UNEP convention on POPs was signed, and "the dirty dozen" - the twelve worst POPs - were banned. However, it will be a terribly long time before the effects of this ban can be traced in the Arctic. It takes something on the order of several hundred years for these substances to circulate with the sea currents in the Arctic Sea.