The Danish-Greenlandic Environmental Cooperation

Slipshod workmanship from Viking Times

The church ruins in Qaqortoq are preserved for the future. Dancea and the A.P. Møller Fund have secured the ruin with a thorough restoration. The walls of Hvalsey Church were built of beautifully fitted ashlar. The foundation, though, is a disgrace.

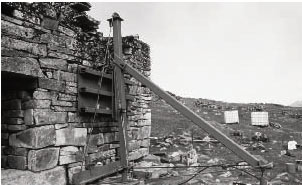

The east gable of the Hvalsey Church ruin. As early as 1721, Hans Egede, on his trip to south Greenland, noticed that the south gable was giving way.

The reason the ruin is still standing where Hvalsey Church was first built in the 1100s in Julianehåb district (Qaqortoq), is because the church was built of stone. This is unique. Churches in Iceland from the same period disappeared a long time ago because they were built of wood or sod. The lack of trees in Greenland has meant that the Hvalsey Church ruins are now a candidate for UNESCO's World Heritage List

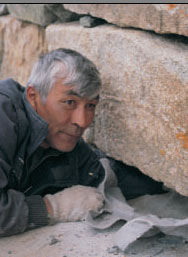

We're talking very big stones. Some of the stones weigh four or five tons; a few are even heavier. The wall is about a meter and a half thick. The stones in the church wall were chosen so carefully, that it was possible to build a solid stone wall by inserting stone chips. Archeologists and building experts are still discussing whether lime mortar was used to cement the stones together. Mortar was used, that much is sure, but perhaps only for grouting. "It seems as if they either had to conserve mortar or that they were not very confident about its carrying capacity," says Søren Abrahamsen, consulting engineer and the driving force behind the whole process of straightening up the falling ruin in Qaqortoq. In any case, the stones were chosen and fitted meticulously.

Restoring the ruin

Restoring a ruin is a delicate task. The church is not to be rebuilt, just stabilized as a ruin. It will not, then have a roof built on it. But is it "cheating" to use modern methods and modern materials? During the restoration of the ruins of Kalø Castle near Rønde on Djursland there was not enough of the original brick. The modern bricks that were used where they were needed are very conspicuous. In Hvalsey, local stone could be used, but the difference between original stone and later stone would be apparent, though not as obvious as with the bricks in the Kalø Castle ruins. This is partly because lichens grow on the side of the stone that faces up when lies on the ground. Nature's own patina. Søren Abrahamsen and others that have investigated the Hvalsey ruin over the years have recorded which stones are original and which have been fitted in at different times in an attempt to stop the south wall from giving way.

The danger of it falling has been noticeable for several hundred years. In 1828, first lieutenant of the army, W.A.Graah, complained that, "Presumably, it is due to the sinking grounds that this wall started tilting, it will hardly be able to resist the ruinous wind for another half century." As much as the prevailing east wind, it is water that has undermined the church. The south wall clearly leans furthest just where the greatest amount of water runs under the church.

The sinking of the south wall probably started very soon after the church was built. At its worst, the south wall tilted 52 cm. The cause: an unsound foundation. In some places the turf had not even been removed. And as the graves that the church was built over gradually collapsed, the south wall of the church followed. Though attention has obviously been lavished on the details on the visible part of the church, the foundation is slipshod work. All in all, it is a case of poor workmanship from the Viking Era.

The white churchThe most famous of all Norse ruins, the ruin of Hvalsey Church, has now been saved for posterity. The National Museum of Greenland with support from Dancea and the A.P. Møller and Wife's Fund for Ordinary Purposes has restored and stabilized the church ruin so it can stand for the next thousand years. The south wall was lifted with a thirty-ton hydraulic jack. The foundation was cast during the lifting.

Qaqortoq means "the white place". The name can probably be attributed to Hvalsey Church, which was originally whitewashed, and, as the dominating building, gave the name to the town at the mouth of the fjord system, where Eric the Red's Brattahlid, the episcopal residence, Gardar and Hvalsey Church itself were located.

The Hvalsey Church ruin is the bestpreserved ruin from the Norse period. But it was not the only church in the area. At least six church ruins have been unearthed. Besides that, a number of private chapels.

The latter were obviously small. It is odd that the building style does not in the least resemble the style used for churches in Iceland. Until modern times, churches in Iceland have all been built of wood or sod, and they have been small. The churches erected during the Norse period in Greenland were relatively large, and built of stone. The walls were built using advanced masonry techniques with alternating thick and thin courses. The Hvalsey Church ruin has windows that widen out towards the inside like funnels, similar to the Anglo-Norman church style. The Norse cannot have learned that in Iceland. However, this building style is known in the British Isles. It is likely that the art of church building came to Greenland from there.

It is not unlikely that the damage was done while the church was being built, as the soil under the foundation collapsed under the heavy weight of the wall.

Latest newsBy chance, Hvalsey Church has become the site of the last documentation of the presence of the Norse in Greenland. On the sixteenth of September 1408, Thorstein Olafssøn married Sigrid Bjørnsdatter in Hvalsey Church. After that the rest is silence about the Norse in Greenland.

Up until the beginning of the 1900s, countless expeditions searched for the descendents of the Greenlandic Norse. In vain.

A thirtyton hydraulic jack was used to stabilize the wall, preserving for posterity the finest memorial of the Norse period.