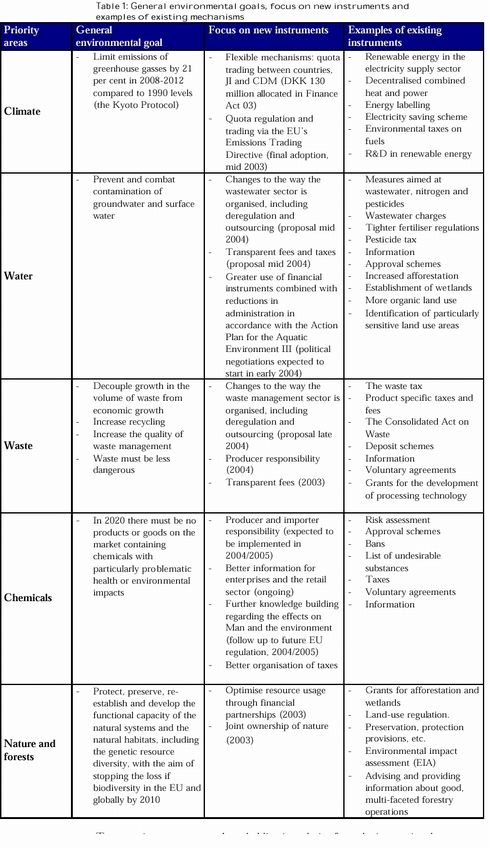

Making Markets Work for Environmental Policies2 Changes of direction in environmental policy2.1 Climate changes2.2 The aquatic environment 2.3 Waste 2.4 Chemicals and products 2.5 Forests and nature An ambitious and responsible environmental policy will meet the environmental goals set – both nationally and internationally. The government takes this responsibility seriously. One example is the climate goal of reducing emissions of greenhouse gasses by 21 per cent in 2008-2012, compared to 1990 levels. The Danish environment goals are described in a number of strategies and action plans and are implemented via Acts and Statutory Orders. The important goals for sustainable development are summarised in Denmark’s national strategy for sustainable development. Table 1 shows the overall environmental goals and the new instruments the government plans to focus on in its efforts to make the market work for environmental policies, along with examples of existing instruments. For each of the new instruments, details are given of the government’s intended proposals. The new instruments are part of a process to make the market work for environmental policies, and will thus continue after the year indicated. A more detailed presentation of each of the five priority areas (climate change, water, waste, chemicals, and nature and forests) is given after the table, later in the chapter. The instruments, objectives, and initiatives already under way in each area are mentioned. The issues have been chosen on the basis of the weighting they have in environmental policy, including expenses and environmental impact.

To a certain extent, our goals and obligations derive from the international conventions and protocols being implemented in Danish legislation. In addition, a significant proportion of our goals and obligations represents the implementation of the EU’s environmental regulation. In the period from 1994 to 2000, over three hundred environmental legislative acts have been adopted in the EU, each requiring transposition in Danish law. The EU’s overall long-term environmental goals for the next 10 years are stated, for example, in the EU’s Sixth Environment Action Programme, adopted by the EU’s Environment Ministers in March 2002. 2.1 Climate changesIn order to combat global warming resulting from greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, nitrous oxide, and three industrial greenhouse gasses), the Kyoto Protocol from 1997 sets specific goals for the reduction of greenhouse gasses to be fulfilled in 2008-2012. Denmark has committed itself to reducing its average annual greenhouse gas emissions in the period 2008-2012 by 21 per cent compared to the base year, 1990. This is an ambitious goal, requiring the selection of cost-effective solutions. If no new initiatives are pursued, it is estimated that the CO2 shortfall will amount to approx. 20-25 million tons of CO2 equivalents annually, or approx. 25-30 per cent of the total Danish greenhouse gas emissions. The CO2 shortfall is the difference between the estimated emissions in the absence of further initiatives and the Danish reduction targets. The costs to society of correcting the shortfall are estimated at between DKK 1-2 billion and DKK 4-5 billion per annum in the five-year period 2008-2012 – depending on which instruments are employed. The instruments employed to date have been national initiatives in the form of energy and transport taxes, subsidies for energy savings and renewable energy, grants for the development of energy technologies, tradable CO2 emissions quotas in Denmark (½ million tonnes in 2001), combined production of heating and power, energy labelling, etc. A more cost-effective solution must also incorporate international instruments and ensure greater choice for enterprises. Objectives The decision base appears in the government’s recently published report: “A cost-effective climate strategy”. Given that the cost range is estimated to be between DKK 1-5 billion annually, it is obvious that the cheapest solutions have to be preferred. The flexible mechanisms under the Kyoto Protocol are: 1. international emissions quota trading,2. implementation of projects to reduce emissions of greenhouse gasses in Eastern Europe – “Joint Implementation” (JI), and 3. implementation of projects to reduce emissions of greenhouse gasses in developing countries – “Clean Development Mechanisms ” (CDM). Consensus has been reached in the EU’s Environment Council regarding a proposed directive on trading CO2 emissions quotas between EU Member States. The directive will involve the introduction of CO2 quotas for enterprises in the energy sector – primarily electricity supply utilities – and a number of energy-intensive industries, from 2005. Each year, these enterprises will be allocated a number of quotas, and will be able to buy and sell quotas in trading with other enterprises anywhere in the EU. The quota system is intended to work together with the project mechanisms. It will thus be up to each enterprise to choose whether they can most effectively meet their own emissions shortfalls through their own reduction initiatives, or by financing reduction initiatives abroad – depending on which is most costeffective. Reduction measures will largely be based on the use of flexible mechanisms. Preliminary estimates suggest that the price for quotas and project credits (JI and CDM) is unlikely to exceed DKK 100 per tonne CO2 in the period 2008- 2012. A price in the range of DKK 40-60 per tonne CO2 is most likely. However, there is a large degree of uncertainty associated with this estimate. It is also based on the assumption that USA will not ratify the Kyoto Protocol. A price level of less than DKK 100 per tonne CO2 means that the flexible mechanisms will lead to greater reductions in CO2 per DKK than most domestic mechanisms. A few national reduction measures are considered to be competitive with the flexible mechanisms in terms of cost – and in some cases, perhaps even cheaper. This applies particularly to limitations for electricity production based on fossil fuels, and a number of energy-savings measures, etc. Most of the remaining national measures involve higher costs. For example, expansions to the use of offshore wind turbines or biomass as a fuel are currently associated with costs of just under DKK 300 per tonne CO2. In order to ensure consistency in reduction measures across sectors, a yardstick has been determined as a basis for implementing domestic initiatives. This yardstick is a CO2 price of DKK 120 per tonne. This will facilitate a balanced approach between the sectors in Denmark for which domestic instruments outside the quota system might possibly be employed. This approach requires that the government is only involved in the overall management of the market. Enterprises must act on the basis of prices and quota limitations, so that the market decides where and how activities should be implemented, i.e. in which sectors, and whether at the domestic or international level. In order to show the way and “kick-start” one market, the government has allocated DKK 130 million in 2003 to purchase credits and establish project reductions in Eastern Europe. The essence of the change of tack on climate change is that initiatives now have to be implemented in the most economical way, while also involving the international market in the form of flexible mechanisms. The narrow focus on individual national measures is being changed to a broader focus, in which the most important mechanism will be the implementation of the Emissions Trading Directive as a general instrument, enabling enterprises to choose the most cost-effective specific measures. Initiatives

2.2 The aquatic environmentClean surface and ground water is an important resource, and water quality has great significance for the population and for use in trade and industry. Water-related tasks represent approx. 25 per cent of the total expenses for environmental initiatives, amounting to DKK 10 billion annually. Water resource management and services are characterised by being primarily user-financed via payment for drinking water and wastewater treatment. Numerous facilities are involved, and the operational tasks are well-defined and delimited. Payments for water resource services vary significantly from municipality to municipality. The government wants to see a user-financed system in which enterprises and residents pay for the service they receive. Industry, towns, and agriculture are contributing to the rapid spread of chemicals into the aquatic environment, damaging the environment and health. Levels of nitrogen and phosphorus leaching are also still considered to be too high. The consequences range from the continued contamination of groundwater to oxygen-depletion problems in coastal regions. Agriculture has a key role to play in the long-term, cost-effective solution of these nutrient-related problems, and is already making an effort. The ongoing development of the agricultural sector contributes to maintaining the need for dynamic environmental initiatives. Pesticide residual contamination in water borings – especially in private wells and boreholes, is a problem. This is primarily the result of pesticides which have already been phased out, but once the groundwater has been contaminated, the damage cannot be undone. Objectives The government intends to create clear incentives to encourage increased cost-effectiveness and greater competition in this area. The organisation of the water supply and wastewater management sectors must therefore be reviewed and assessed in order to achieve greater cost-effectiveness. The aquatic environment initiatives will be a collection of measures to 1) prevent further contamination of the aquatic environment resulting from society’s activities, 2) ensure the operation and maintenance of sewers and waste water treatment plants, and 3) reduce the env ironmental and health impacts from contamination from earlier periods. The government’s guiding principle is that the initiatives must be economically appropriate. One important general element is that the EU has adopted a new Water Framework Directive for water resource initiatives. The directive replaces a number of earlier individual directives and in this respect represents a deregulation of the area. Amongst other things, the directive aims at ensuring joint and more binding efforts in the area of transboundary contamination. This problem is relevant, for example, in relation to the protection of Danish coastal waters, which are affected by activities in the entire drainage area. The Water Framework Directive requires Denmark to make greater efforts to protect the aquatic environment, especially in heavily impacted aquatic environments such as the Limfjord and Mariager fjords. The Water Framework Directive should be implemented in a way that leads to the improved cost-effectiveness of environmental policies. The government is therefore investigating the possibility of using the new directive to implement more cost-effective initiatives in the entire area of water services and water resource management. In order to prepare for this, a number of economic and organisational analyses of the water sector have been launched and are expected to be completed in 2004. Public wastewater management costs approx. DKK 5 billion annually for operation, maintenance, and renovation of sewers and treatment plants. These activities are primarily carried out by the municipalities and are fully user-financed. The government has the goal of greater transparency for residents and enterprises in terms of what they are paying for. Investigations suggest that the municipalities are delaying maintenance and renovation of the sewer network to an extent that is economically inappropriate. There is therefore a need for greater transparency in relation to municipal expenditure on wastewater treatment, for more competition within the municipal wastewater-management sector, and to consider merging the small municipal entities into larger companies with the expertise and resources to carry out the necessary renovation and provide the necessary services. The options for organising the task differently should therefore be investigated, for example, separating the municipalities’ supervisory and operational roles. The options for outsourcing the operation and maintenance of sewers and treatment plants should also be considered. It is believed that outsourcing the provision of these services would create a better basis for Danish enterprises to develop products, technology, and expertise to help do the work better and more cost-effectively. The government will invite the parties of the Folketing to the negotiation of Action Plan for the Aquatic Environment III. The central goal is to renew and improve efforts to reduce the impact from nitrogen and phosphorus from agriculture, and to ensure that Denmark fulfils the EU requirements in this area. In order to provide a good decision basis for Action Plan for the Aquatic Environment III, three working groups have been established to analyse the use of various types of measures, including market-based mechanisms. General consideration will be given to whether (and how) regulation of the area can be simplified and made more transparent for agriculture, and how it can be structured to give maximum scope to each farmer to choose the most cost-effective solutions. Assessments will also be made of the options for replacing regulation with financial instruments, including taxes and tradable quotas. The possibility of introducing taxes on nutrient losses or tradable nitrogen quotas will be evaluated. A reform of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy subsidy schemes has high priority and will reduce environmental impacts. If the direct connection between subsidies and the scale of production can be broken, this may in itself lead to a more environmentally-friendly utilisation of resources. The government will strive to ensure that EU budget resources from direct subsidies are transferred to initiatives in rural areas, including nature and environment activities and food safety. An evaluation of the Action Plan for Pesticides II will be carried out in 2003. This will include an assessment of goal performance and the instruments utilised, as well as an assessment of the economic consequences of the plan. To ensure priority efforts are made across all areas, the government will incorporate all aspects of the use of pesticides into the new pesticide strategy. This will make it possible to see the future initiatives in context and help target them to the areas in which the environmental and health impacts are greatest. This broad approach will also make it easier to select the most economically effective measures. Organic production makes an important contribution to improving sustainable development in agricultural production. The government would like to see the organic sector continue to develop, based on consumer demand and common EU regulations. The ’Export strategy for organic products’ prepared by the Organic Foods Council has provided the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, the organic organisations, and enterprises, with a solid foundation for future market-based initiatives to promote exports of organic food.

2.3 WasteEconomic development and our production and consumption patterns have a great impact on the volume and composition of waste. Today, waste management facilities have to process very complex products. As a result, our waste processing plants require ever-larger capital investment. Waste management is an important part of environmental policy. The cost associated with the collection and processing of waste accounts for almost one-third of total public environmental expenditure. Most of the tasks are user-financed and subject to the principle of cost coverage. The municipalities have practical responsibility for the services and charge a waste-disposal fee to cover the costs associated with the waste management attended by the municipalities, but the costs vary greatly between municipalities. The area of waste management is characterised by too little competition and too much bureaucracy. It is too difficult for citizens and enterprises to see what they are getting for their money when they dispose of their waste, and there is a lack of incentives to make the sector more cost-effective. Individuals and enterprises whish to have more choices and more flexible schemes. Objectives The government wants to see a more efficient and cost-aware waste management sector, with a high environment profile. This goal is to be achieved by simplifying regulations, increasing fee transparency, outsourcing, and producer responsibility. Today there are more than 8,000 municipal rules and regulations in the area of waste management. This complexity is a significant barrier to the entry of private players into the market, and is a clear burden for carriers and enterprises that operate across municipalities in particular. A simplification of the municipal waste management regulations would lead to better competition conditions for players and make it easier to compare fees between municipalities. There is a potential for efficiency improvements in the area of incineration and landfilling. The advantages and disadvantages associated with various degrees of deregulation of landfilling and incineration facilities are currently being investigated. Deregulation and outsourcing do not intrinsically make market players give greater consideration to the environment, as, for example, a tax does. But deregulation and outsourcing can lead to greater competition, and hence improved efficiency. They are instruments that can help realise the potential for rationalisation already observed.These projects have been initiated by the working group for the organisation of the waste management sector, appointed by the government. At the end of 2004, this working group must make recommendations for how the organisation of the waste management sector can be made more efficient. One example of an efficiency gain from deregulation might be that certain waste fractions could be referred to a particular type of processing, e.g. incineration, rather than to a particular facility, as is the case today. Producer responsibility can be economically appropriate in a number of areas, for example, for cars and electronic goods. When producers or importers have responsibility for handling the disposal of their products, they will seek to reduce their waste management costs by producing environmentally friendly products. Producer responsibility means that producers are given responsibility for organising and financing waste management. Increasing product complexity and processing requirements are placing demands on the development of new processing technologies. Some technologies are now mature enough to be used in full-scale under market conditions. This development is essential in order to achieve better and cheaper waste management in the future. In addition to these initiatives to ensure a more efficient waste management sector, the government is preparing a new waste management strategy for the period 2005-2008. This new strategy will focus on reducing the volume of waste and its environmental impact, but the government also emphasises that changes to current initiatives will only be made if there are socio-economic benefits. The strategy will define the framework for future municipal waste management planning and set out the national waste management goals and instruments compulsory for EU Member States in a more concrete form. Under the new strategy, the government will place greater focus on the magnitude of the environmental problems and the negative socio-economic impacts associated with waste, rather than simply on waste volumes. The central instruments will be taxes, producer responsibility, voluntary agreements, and information. The decision base for new initiatives must be supported by environmental and socio-economic analyses, to ensure that environmental benefits are weighed against costs in a structured way and that the most cost-effective solution is chosen. Investigations are also needed to determine whether the waste tax can become a more targeted instrument. This will be done by examining whether the tax rates adequately support waste policy. An alternative to taxes could be tradable quotas, and the options for using such quotas are also being investigated. Voluntary agreements have been established in the area of waste management, for example, relating to the processing of used tyres and refrigerators containing CFC‘s, selective demolition of buildings, and transport packaging recycling. The possibilities for making use of voluntary agreements in other areas will be examined. Initiatives

2.4 Chemicals and productsIn Denmark, approx. 20,000 different chemical substances and around 100,000 preparations are used. Added to this are the chemicals contained in approx. 200,000 industrial goods. For most chemicals, there is currently insufficient knowledge about their impacts on human health and the environment, and we do not know enough about which chemicals are contained in the products we purchase and use. The EU chemical regulations are basically a harmonisation of the legislation in all the Member States, and the Danish chemical regulations are therefore often directly linked to international regulations, agreements or cooperation. The current Danish regulations employ administrative instruments in the form of bans, restrictions on uses, and approvals, supplemented by voluntary agreements and information. Due to the harmonisation of legislation, there is not much room, domestically, to introduce restrictions on use. Any such national regulations must be well-documented and must accommodate the rules concerning the free movement of goods. At the same time, the instruments that least distort competition must be used. These might be, for example, taxes on chemicals. Objectives In the EU, it has so far been the task of the Member States to investigate and assess the risk of chemicals before any regulations are introduced. This work is extensive, and information about product contents and properties is not always available to the authorities. Therefore, in early 2003, the Commission will present a proposal for a completely new way of regulating chemicals, promising clear efficiency improvements. The most significant change is that, in future, the chemical industry will be required to investigate and evaluate chemicals itself. The authorities will continue to be responsible for the actual approval process. Once industry, rather than the authorities, is responsible for ensuring chemicals can be produced and used safely, it can be expected that environmental improvements will be arranged in the best and cheapest way possible. The industry has detailed knowledge about the production of the chemicals and their properties, etc., and it can therefore determine how the risk can be limited. The EU will also soon introduce an authorisation scheme for particularly dangerous substances. This implies that industry will no longer be automatically permitted to use particularly dangerous substances, but will have to seek approval and prove that it is safe to use the notified chemicals. Danish enterprises that produce, import, or use chemicals will gain a competitive advantage if they are informed of the new EU chemical regulations as early as possible, so that they can plan the most cost-effective approach ahead of time. Once the new EU chemical regulations are in place, it is expected that the need to introduce purely national regulations restricting uses will fall dramatically. Denmark has previously introduced a number of national chemical regulations in areas not yet covered by any EU regulations. This has been very burdensome, not just at the administrative level, but also for Danish enterprises. There is particular focus in Denmark on the analysis of chemicals in consumer products and endocrine disrupters, since uncertainty about the possible harmful impacts from these substances on humans and the environment is causing concern. Efforts are being focused on investigating the extent to which consumers are exposed to chemicals, analysing where the particularly problematic substances are found, and informing consumers, purchasers, and the retail sector about the findings. The “List of undesirable substances” is to be updated in 2003. This list identifies the substances future initiatives will be directed towards, including substances expected to be covered by the forthcoming EU authorisation scheme. Danish enterprises need to be able to see an advantage in changing to less harmful substances. The “List of undesirable substances” will highlight a group of high priority substances/substance groups for which specific initiatives are required to reduce their application. The initiatives will be planned separately for each priority substance/substance group. The mechanisms are most often product-related, for example, recommendations to consumers to use eco-labelled products which either do not contain the undesirable substances, or do so only in small quantities. Initiatives The new EU regulations:

National market-oriented initiatives:

2.5 Forests and natureThe development of the Danish society throughout the last century has led to increasingly difficult conditions for nature. In order to ensure an appropriate level of conservation, Denmark has made use of a diversified regulation of its natural resources. This regulation is supplemented by a number of international obligations which place demands on Denmark’s nature conservation efforts. The challenge is to continue to optimise and rationalise the total regulation of nature conservation within these frameworks, in an economically reasonable manner. There is also a need to ensure a reasonable balance between the requirements and wishes of the population, and conditions for land owners, associated enterprises, and total land use. Objectives The majority of the country’s open spaces and nature areas are privately owned, and the government will seek to supplement existing regulations or replace them with self-regulating or self-financing measures. The government is also emphasising the increased involvement of local stakeholders and better dialogue with residents about the content and quality of nature conservation. One model for market-based regulation of nature conservation could be to introduce the right for owners to charge a fee for access to heaths, forests, and beaches. However, the model is not directly feasible, since it is in fundamental conflict with the established right of public access. Therefore, the initiatives relating to private land owners must be directed towards other options for creating or exposing marketable assets. The regulations thus need to be simplified to increase opportunities for owners to produce and sell natural assets to a greater extent (hunts, horse riding, and other nature activities). Work on labelling of forestry products needs to be further developed in cooperation with businesses and organisations, assuming it is found to be possible to obtain higher prices for labelled products. In a proposed EU directive on environmental liability, the ’polluter pays’ principle is expected to be extended to cover damage to biodiversity and nature. The implementation of this directive is expected to provide opportunity for partial market-based regulation through the establishment of private insurance schemes to manage compensation payments and measures. As far as the government’s activities in the area of nature conservation/biodiversity are concerned, initiatives will be based on socioeconomic principles. In order to achieve more comprehensive results, in future, the provision of public assets in the form of public forests and nature areas, with recreation, communication and information facilities, and activities, will be based to a greater extent on partnerships and joint ownership between public and private stakeholders. One example is municipal co-financing of afforestation projects, where a positive economic synergy effect is achieved between two environmental goals – clean drinking water and public nature recreation areas. Initiatives

_____________________________________________________________________ |