|

Waste Strategy 2005-08 Appendix B Volumes of waste and statistical base

B.1 Developments in volumes of wasteB.1.1 StatusAims for 2008

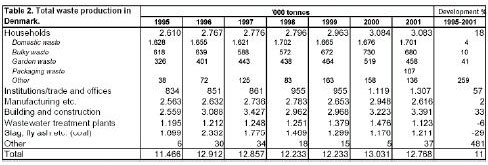

In Denmark, 12.8 million tonnes of waste were generated in 2001 (see Table 1). This represents a 2 per cent fall in waste generation compared to the previous year. This fall is primarily due to the fact that sludge for mineralisation began to be reported using a dry matter content of 20 per cent in 2001. In previous years, the dry matter content has been 1.5 per cent. Part of the fall is also attributable to the fact that the volume from production enterprises has fallen by 11 per cent compared to 2000. A large proportion of this fall is due to a reduction of over 200,000 tonnes in the volume of iron and metal scrap, compared to 2000. The volume of waste from the service sector has risen by 17 per cent compared to 2000. There has been a general rise in all waste fractions within the service sector. It is important to realise that changes were made to the categorisation of sectors in the Environmental Protection Agency's ISAG system [1] in 2001. These changes have led to a significant break in the data in 2001, in relation to the previous years. Comparisons at the sector level between volumes of waste for 2001 and previous years must therefore be made with a degree of caution. Table 1 specifies the distribution of waste generation for 1995-2001 by source. Source: Waste Statistics 2001, Danish Environmental Protection Agency 2003. Figure 1 shows the treatment of waste in Denmark, compared with the goals in Waste 21. In 2001, 8,101,000 tonnes (63 per cent of the total volume of waste) was recycled.

The storage figure refers to waste suitable for incineration that is temporarily stored until the necessary incineration capacity is available. Source: Waste Statistics 2001, Danish Environmental Protection Agency 2003. The volume of waste incinerated in 2001 was 3,221,000 tonnes or 26 per cent of the total volume. The landfilled volume of waste in 2001 was 1,317,000 tonnes (equivalent to 10 per cent of the total volume of waste). In 2001, 1 per cent of waste was given special treatment. It is primarily the high recycling rate for construction and demolition waste and residues from coal-fired power plants that has contributed to the high overall recycling rate. B.1.2 Developments in volumes of wasteThe development in volumes of waste from 1995 to 2001 is shown in table 2. From 1995 to 2001, the total volume of waste rose by 11 per cent. The volumes of waste rose throughout the period for all sectors, except for slag, fly ash, etc. from coal-fired power plants and sludge for mineralisation from wastewater treatment plants. The volume of residues from coal-fired power plants has fallen as a result of the goal in Energy 21 to continue to shift from the use of coal and coke as fuel to natural gas and renewable energy. The volume of residues from coal-fired power plants depends not only on energy consumption in Denmark but also on electricity exports to Sweden and Norway.

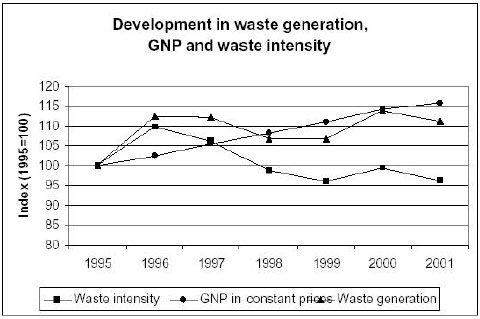

Source: Waste Statistics 2001, Danish Environmental Protection Agency 2003. The figure below shows that the total volume of waste increased more rapidly than economic growth in the period 1995 to 1996. This was followed by a decline in the volume of waste, and another increase during 1999 to 2001. However, this is only the picture for the total volume of waste. Appendix D shows the development in volumes of waste for each sector. Waste generation is the result of all activities in society. If total waste generation is shown in proportion to gross national product (GNP), it provides an indication of the waste intensity in society.

Source: Waste Statistics 2001, Danish Environmental Protection Agency 2003, Statistics Denmark. The graph shows the relative changes in gross national product in constant prices [2] (GNP), waste generation and waste intensity, which is the relationship between the relative change in waste generation and the relative change in GNP. As can be seen in the figure, waste intensity declined until 1999 (decoupling) and has subsequently been relatively constant. This means that growth in the volume of waste during this period has largely corresponded to growth in GNP. Thus this trend does not point in the direction of decoupling, but rather an approximately constant relationship between growth in the volume of waste and growth in GNP. B 1.2.1 Forecast 2000 – 2020A forecast has been prepared for volumes of waste through to 2020 using the Risø model. This forecast is based on the Financial Statement and Budget Report 2001, the Danish Energy Authority's latest forecast from March 2001, and an adjustment of the model to ISAG data for 2000. Waste 21 sets out a number of objectives for waste treatment through to 2004. Many of the initiatives in Waste 21 involve increased sorting for certain waste fractions with the aim of moving waste from incineration to recycling. But an equally important goal in Waste 21 is to stabilise the total volume of waste. The forecast is based on the assumption that the initiatives in Waste 21 relating to increased separation and recycling of paper and cardboard, glass, plastic and organic waste will be implemented between 2000 and 2004. No further assumptions have been made about increased separation for the period 2004 –2020. This period is thus purely based on the models own forecasting ability. This means that the initiatives in this Strategy have not been included in the forecasts. Note that the Waste 21 initiative relating to the recycling of organic domestic waste has not been implemented, with the result that the forecast for recycling has been set too high. A quite large increase in the volumes of waste is predicted because animal waste (approx. 200,000 tonnes of meat-and-bone meal) from industry will be shifted to waste incineration plants. Future volumes of waste will also contain ocean floor sediment. These waste fractions have not previously been recorded in waste statistics and have therefore not been included in the forecasts. Figure 3. Developments in waste generation, historical data 1994-2000, projections 2001-2020. Waste 21. The figures below compare the forecasts, with and without the consequences of the Waste 21 initiatives. They primarily show a reduction in the volume of the mixed fraction "waste suitable for incineration, and an increase in the volume of the recycled fractions, paper and cardboard, glass, and plastic, cf. figure 4 and 5.

If no further initiatives are introduced to influence the development in volumes of waste after 2004 [3], the Waste 21 corrections for 2000 – 2004 mean that the proportion of waste that will be incinerated in 2020 is reduced from 26.4 per cent to 24.6 per cent, while the volume of waste that will be recycled is increased from 62.5 per cent to 64.4 per cent. In other words, Waste 21 ensures that the proportion of recyclable fractions is the same in 2000 and 2020, such that the distribution between forms of treatment will basically be the same in 2000 and 2020, cf. figure 6. Without the initiatives from Waste 21 there would be a decreasing proportion of fractions recycled.

B.2 Statistical baseB.2.1 StatusAims for 2008

There is a need to continue the systematic collection of comparable data on waste generation and treatment at a detailed level and in a way that enables both enterprises and local and national authorities to use this data. This need will increase in future, as more and more waste fractions become subject to special treatment. A central data reporting system exists (Information System for Waste and Recycling - ISAG) which each year provides a good picture of the waste generated in Denmark and how it is treated. ISAG was launched in 1993. Waste managers report waste data to the ISAG database [4] each year. This database is administered by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency. The aim of ISAG is to provide a statistical basis for analysis and planning purposes. ISAG extracts are sent to the municipalities every year to be used in the preparation of municipal waste plans, and are also used by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency in preparing action plans and waste management initiatives. ISAG data is also used to fulfil Denmark's international reporting obligations. ISAG is continually being extended. The latest change to the system involves expansion with more detailed information on plant capacity, operational data, treatment prices, geographic sources of recyclable waste, further detail for the trade and industry source, extended information on hazardous waste and waste carriers. ISAG provides a good overview of the development in volumes of waste, but cannot be used to monitor individual flows of waste at a detailed level. ISAG data is not sufficiently detailed to be used for reporting to the EU. In parallel with ISAG, more detailed knowledge on various waste fractions is therefore regularly collected in the form of material flow analyses [5], etc. Investigation is currently being made into what correlations exist between these material flow analyses and ISAG data, and whether ISAG data reports can replace some of the data collected for material flow analyses. Under the Statutory Order on Waste, Waste carriers are required to keep a register containing information about waste shipments. The aim of the register is to function as an inspection tool, and the data must be reported to the municipalities as required. No uniform requirements have been laid down for the form of this registration by the carriers. Each municipality lays down requirements for the form and content of the register in regulations. This means that carriers may have to report data in different ways to different municipalities. Under the Statutory Order on Waste, waste generating enterprises must keep a register of the waste they generate so that they are able to prepare source cards and report this information to the authorities (national, county and municipal) upon request. This registration of waste data at each stage serves various purposes. Registrations at the producer and carrier stage primarily serve an inspection purpose while the ISAG registrations at waste treatment facilities provide more general information between the three stages. There are differences between the types of information and the volume and level of detail. There will continue to be a need to carry out material and mass-flow analyses for selected waste fractions. This will particularly be the case for areas where the general data registration (ISAG) is not adequate. The Danish Environmental Protection Agency has developed and calculated new waste indicators for resource consumption, energy consumption and landfill requirements for various treatments (re-use, recycling, incineration and landfill) for a number of materials in waste [6]. Energy consumption is used in this context as a combined indicator for both the greenhouse effect and acidification. Calculation of the indicators is based on life-cycle analysis data (LCA data). When initiatives aimed at various materials in waste, such as glass or aluminium, need to be prioritised, one can compare the indicators for resource consumption, energy consumption, and landfill requirements for these materials and thereby compare the environmental factors for the various materials. The new indicators require a very large LCA statistical base, analysis of material flows and complicated calculations. The resulting indicators are therefore subject to greater uncertainty and will not be as robust as the existing waste indicator for volume of waste in tonnes. It takes time to obtain data and calculate the new indicators. The first set of indicators for a number of waste fractions were presented at the beginning of 2003. The indicators can only be fully utilised to illustrate waste management developments once a series of calculated indicators has been accumulated over a number of years. However, the new indicators can already be used to guide the selection of waste fractions to be targeted by initiatives and the most suitable forms of treatment for these waste fractions. In this way, the new indicators can be used to select where we achieve the best environmental results with the resources available. Initially, three indicators have been calculated:

These indicators have been calculated for the existing waste treatment of the various waste fractions and for optimal treatment, where it is assumed that recycling will be increased to a realistic level, taking into account both technological possibilities for increased recycling, and realistic options for collecting each particular waste fraction. The indicators reveal what is saved by using each form of treatment, compared to 100 per cent landfilling of the particular waste fraction. Unfortunately, the three new indicators cannot be calculated for all waste fractions due to a lack of LCA data. For example, for the building materials (concrete, tiles and asphalt), data relating to resource and energy consumption during raw material extraction and recycling is not available. For plastic, data is only available for the recycling of PE, which has therefore been used for all plastic types. Similarly, up-to-date data and other data are not available for several metals. There can be other significant environmental and societal factors apart from resource consumption, energy consumption, and landfill requirements. For example, nutrient salt load, and human and ecotoxic effects. Toxic effects are obviously of greatest significance for the hazardous waste fractions. Since LCA data is not available for these effects, new waste indicators have simply not been calculated for these hazardous waste fractions. When making final decisions about and ranking new initiatives targeting individual materials in waste, it is important not to focus on the new indicators alone. At the very least, a qualitative assessment of hazardous emissions from the processes in the material's life cycle must be carried out before significant decisions are made on the basis of the indicator values. There is a great need in the future to supplement the LCA databases with data for recycling processes, and especially for human and ecotoxic effects. Chapter 2 presents an overview of the new waste indicators for resource savings, energy savings, and savings in landfill requirements for existing waste treatment and the unexploited potential for further savings. The indicator values calculated for each material, from which the waste indicators are derived, are shown in the individual fraction sections in Appendix E. B.2.2 Future initiativesMeasures:

Knowledge-sharing is a central instrument to be used by the players when implementing the Waste Strategy. Information can support and contribute to fulfilling the various elements of the Strategy. Relevant information must be made available to the players via the Internet and other media. Waste Centre Denmark has a central role to play in this area, and it is important that the Waste Centre can continue to promote knowledge-sharing between players in the area of waste management. The centre is supported by funding in the annual budget. In 2002, the Minister for the Environment appointed a work group to examine the organisation of waste management. One of the group's tasks was to look at registration and reporting requirements, with the aim of simplifying these. The group was also to investigate whether reporting obligations would be streamlined if a central database was established, to which all relevant information was reported once a year. Initiatives that support the development of methods that can measure the effect of initiatives on reducing environmental impacts in waste management, for example by measuring heavy metals in residues, will be promoted. Mass-flow analyses will be prepared in areas were ISAG registrations are not sufficient. More work is to be done with the new waste indicators for resource consumption, energy consumption, and landfill requirements. If LCA data can be obtained for resource and energy consumption during both raw material extraction and recycling, the indicators will be calculated for building materials. LCA data must also be sought for all plastic types, for various metals, and for the new treatment methods for PVC and impregnated wood. There can be other significant environmental and societal factors apart from resource consumption, energy consumption, and landfill requirements. For example, nutrient salt load, and human and ecotoxic effects. Toxic effects are obviously of greatest significance for the hazardous waste fractions. If LCA data becomes available for these effects, new waste indicators will be calculated for these hazardous waste fractions. The waste indicators will be compared with cost-benefit analyses. This will provide a solid basis for assessing whether the specific waste fractions are being treated in the most environmentally and cost-effective manner. B.2.3 RegulationGeneral information on waste is collected via the Information System for Waste and Recycling (ISAG), launched in 1993. ISAG is administered by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency. Under the Statutory Order on Waste, waste treatment facilities must report information about the waste they treat to the Environmental Protection Agency. B.2.4 Environmental assessmentThe waste indicators for resource consumption, energy consumption, and landfill requirements will provide an improved foundation for selecting the best environmental initiatives in the future. B.2.5 Financial estimateCalculation of the three indicators shown in Chapter 2 and Appendix E has cost DKK 1.2 million. It is estimated that it will possible to update the indicators for approx. DKK 0.5 million each time. The costs of extending the indicator system depend on the availability of data and cannot be estimated on the existing basis. B.2.6 Implications for the national authoritiesThe work group will analyse the data registration and reporting obligations to investigate whether it is possible to simplify the entire data collection system. Simplification of the registration and reporting obligations would reduce the burden on all players involved in waste management. The Ministry of the Environment will update the indicators every two to three years. ISAG data and material flow analyses will be used to carry out the necessary data reporting to the EU. B.2.7 Implications for municipal authoritiesMunicipalities will use a central database as a basis for municipal waste management planning, and to carry out supervision of waste management in the municipality. B.3 Technological development in waste managementB.3.1 StatusAims for 2008

The quality of waste treatment must be improved. Better quality in waste treatment requires the development of new technologies. Denmark has been at the forefront of waste treatment technology development and continues to keep abreast of global developments. If technologies suitable for managing waste of the future are to be developed in general, an intensive effort is required to solve the task systematically. It will be necessary for the state to get involved in this work. Municipalities are responsible for waste management. This makes them important players in the identification of new waste types for separate treatment, the establishment of new logistical systems, and the selection of technologies for the treatment of waste. Profitable treatment of waste requires that plants have sufficient supply and a sound financial basis. The need for sufficient supply will, for example, require that small waste fractions be collected from larger areas. Cooperation across borders or within sectors with many small enterprises may be the key to creating the necessary basis for recycling these fractions. It may be necessary to establish a small number of plants for the treatment of certain waste streams. The location of such plants must be matched to supply conditions and logistics. Technological development does not happen automatically in the waste management. This is partly because the necessary quantities of waste for treatment are not always available. For example, one waste fraction may be generated in small quantities in all municipalities. Other waste fractions may arise in large quantities in few municipalities. The supply base can therefore be uncertain. This creates barriers to innovation and the development of profitable collection systems and treatment methods. It also means there is no incentive to invest in the development of new plants and put them to commercial use. With funding from the Council for Recycling and Cleaner Technology and the Environmental Council for Cleaner Products, a number of investigation and development projects have been carried out over the last eight years. These projects have led to the development of technologies on a pilot or industrial scale, that can reprocess PVC and flame-retardant plastic, impregnated wood, shredder waste, flue gas cleaning products from waste incineration plants, and batteries. However, the results have not led to the establishment of reprocessing facilities on an industrial scale. For this reason, the Environmental Protection Agency has initiated an investigation into what initiatives are required in order to establish the technologies developed on an industrial scale. The volumes of waste that will be available in Denmark have been investigated. The costs of reprocessing the waste fraction have been compared to the existing treatment of the waste, potential investors have been identified, and the conditions under which they would be willing to invest in future reprocessing facilities have been assessed. The results show that investors do exist, but that national regulations, including reprocessing quality requirements, are necessary before they will be willing to inject the necessary capital. To ensure that treatment technologies continue to be developed, the state must provide continued support for such development and lay down requirements for waste treatment once technologies exist so that plants can be established and operated under market conditions. The EU support program, LIFE-Environment, is a possible source of funding in this area. For example, in 2001, approx. DKK 28 million was given from this source to support a Danish demonstration project for the recycling of PVC waste using thermal hydrolysis. There is a general need to provide a boost to this area so that waste treatment is developed throughout the whole country. This initiative requires innovation, both in terms of technology and organisation, and it is necessary that improvements be nationwide. B.3.2 Future initiativesMeasures

It is expected that grants will continue to be made to development projects that contribute to the development of new treatment technologies. Technological development within waste management will be supported. In cooperation with the players, the Environmental Protection Agency will evaluate areas where there is a need for greater efforts and how best to support these efforts. A central area in relation to these initiatives will be to lay down reprocessing requirements for the various waste fractions on the basis of existing technology. These reprocessing requirements should be set on the basis of environmental and cost-benefit analyses. B.3.3 EconomyFinancing requirements are covered to a limited extent by funds from the Environmental Council for Cleaner Products. However, the Council is not currently able to provide grants for plant investments. There is a need to examine which other financing possibilities can be established in order to enhance technology development. The possibility of obtaining funds from private enterprises will be investigated. B.4 Economic and environmental effects of waste treatmentB.4.1 Costs of waste managementThe costs of waste management can be divided generally into treatment costs, collection costs, and waste tax to the state. These costs are often collected as a total fee from residents and smaller enterprises covered by collection schemes. In 2001, total municipal costs for waste management amounted to DKK 3.9 million. Several investigations have shown that it is impossible to compare the municipal waste collection fees. Enterprises covered by assignment schemes cover the costs of transport themselves and hence the treatment price for assignment schemes does not include transport costs. Municipal expenses for waste management and the finances of public treatment facilities must be based on the non-profit cost-coverage principle, such that the fees collected match the actual expenses. Waste tax The waste tax (see Appendix A) is differentiated depending on whether the waste goes to landfilling or incineration. For incineration, the tax is DKK 330/tonne, while for landfilling the tax is DKK 370/tonne. Recycled waste is not subject to tax. Hazardous waste, contaminated soil requiring special landfilling, and biomass waste are exempt from the waste tax. In 2001, revenue from the tax exceeded DKK 1 billion. The total volume of waste, divided between forms of treatment, is shown in the figure below: Volumes of waste in 2001 [7]

As the figure shows, the major proportion of waste was recycled in 2001. The financial incentives provided by the waste tax are believed to be a significant reason behind the high rate of recycling. Note, however, that the data is based on the total volume of waste and not exclusively on waste subject to the tax. Treatment charges – incineration and landfilling In 2002, the Environmental Protection Agency commissioned an analysis of the potential to rationalise Danish incineration plants and landfill sites (the results of the analysis are discussed below [8]). As part of this analysis, an overview of the size of treatment charges was generated, i.e. the price for delivering waste to a treatment facility, excluding waste tax and VAT. The treatment charge for incineration varied between DKK 0 and over DKK 900 per tonne, with the average treatment charge for incineration being DKK 248 per tonne, excluding waste tax and VAT [9]. The treatment charge for landfilling varied between DKK 100 and DKK 750 per tonne, with the average treatment charge being DKK 233, excluding waste tax and VAT [10]. A report from the European Environment Agency shows that compared to other European countries, the Danish treatment charges for incineration and landfilling are low. For example, the price for incineration in Germany is approx. twice as high as in Denmark [11]. Market price for treatment – recycling There is no systematic overview of treatment prices for recycled waste. This is because recycling typically takes place in the private sector and the recycling method varies greatly depending on which waste fraction is involved. For example, recycling includes using residues from waste incineration plants in roads, or remelting metals to make new products. Finally, prices fluctuate greatly depending on specific market factors. For example, the prices of metals vary depending on the metal quality and the prices on commodity exchanges. The prices below illustrate the range of market prices that exist for treatment of recyclable/reprocessed materials.

B.4.2 Environment economicsA number of initiatives have been commenced under Waste 21 for which the final decision about implementation of measures will depend on the investigations of environmental and economic factors currently underway. This applies to initiatives such as: Completed projects Organic domestic waste In 2002, the Danish Environmental Protection Agency prepared an analysis into increased collection of organic domestic waste for recycling, compared to incineration with energy recovery. The purpose of the analysis was to investigate both the direct environmental and economic effects and the welfare-economic consequences of increasing the proportion of organic domestic waste recycled. The results of the analysis show that the increased costs of two-part collection are very great in proportion to the environmental effects achieved. The total increase to welfare-economic expenses from introducing the Waste 21 long-term goal of biogasification of 300,000 tonnes of collected organic domestic waste, in relation to the costs of incineration, is in the order of DKK 230 million. An equivalent expansion of composting would cost approx. DKK 270 million. The Waste 21 goal for biogasification in 2004 of recycling 100,000 tonnes would cost of the order of DKK 70 million extra in relation to the existing treatment of organic waste, whereas an expansion using composting would cost approx DKK 80 million. Plastic containers The analysis compares the incineration and recycling of waste plastic bottles and containers from households. The analysis shows that separate collection and recycling is more expensive from a welfare-economic perspective than the existing treatment – incineration with energy recovery. With a low-budget collection system delivering to recycling centres, it would cost approx. DKK 300/tonne more to collect and export for recycling than to incinerate. It is even more expensive to treat plastic waste in Denmark than it is to export it for treatment abroad. Since the analysis was completed, it has been found that it is possible to significantly reduce the costs of sorting the collected plastic containers. It is therefore planned to update the analysis's results with the latest knowledge in 2003, and it is assumed that this will change the results. Efficiency analysis An analysis of the potential to rationalise Danish incineration plants and landfill sites has also been carried out. This analysis showed that there was a potential to realise savings of DKK 135-155 million in the area of incineration in 2000, equivalent to 8-10 per cent of total expenses. This represents a relatively modest potential. In the area of landfill, there is a potential to realise savings of DKK 55-90 million annually, equivalent to an average of 25-40 per cent of total expenses. This represents a relative large potential as a proportion, but less in absolute terms than for incineration. Future projects Future projects There are also a number of environment-economic investigations underway, the results of which are not yet available. These are described below. Cost-benefit investigations for PVC The Danish Environmental Protection Agency is currently in the process of carrying out an environment and cost-benefit investigation of various treatment methods for PVC. The investigation includes an analysis of the various treatment technologies – reprocessing at various facilities, landfilling and incineration. It also includes an evaluation of whether increased separation for reprocessing of PVC waste can be justified in terms of costs and benefits. Deregulation project As an extension to the Efficiency Project, there is a need for closer investigation of the consequences of deregulating waste incineration and landfilling. The goal is to investigate whether it is possible to achieve greater socio-economic efficiency via deregulation of waste incineration and landfilling, without consumer and environmental protection considerations being neglected. The project is expected to be completed mid-2004. Fees This project aims to generate proposals for how fee regulations can be changed to achieve transparency in fees. The project is being carried out in ongoing dialogue with the work group on the organisation of the waste management sector. The project is expected to be completed mid-2003. Dioxin investigation The National Environmental Research Institute, Denmark (NERI) has prepared a report for the Nordic Council of Ministers' work group for products and waste (the PA group) aimed at evaluating the results of existing economic valuation investigations into the costs of impacts from waste treatment, and evaluating final treatment charges on waste in the Nordic countries. Another objective has been to extend the existing knowledge relating to valuation of the external effects of low-dose emissions from waste incineration. It was decided to focus specifically on dioxin emissions. There are also a number of pending projects that have not yet been initiated. The following projects will be initiated this year, and their results are expected to be available within the first part of the Strategy period. Due to the significant development in treatment technologies for PVC, impregnated wood, shredder waste, and acidic flue gas cleaning products, it is necessary to evaluate from a cost-benefit perspective whether the environmental effects resulting from reprocessing waste fractions are in line with the expenses. The analysis of impregnated wood (like the analysis underway for PVC) aims to identify the economic and environmental consequences of increased recycling and evaluate whether there are critical differences in either the environmental effects or expenses associated with establishing full-scale facilities using various technologies. The analyses for shredder waste and acidic flue gas cleaning products will exclusively evaluate the choice of treatment methods in connection with available technologies. These investigations are thus purely related to technology selection and not the magnitude of the recycling potential or the expenses linked to exploiting it. The reason for this is that there are relatively few sources with large volumes of waste. Use of quotas The objective of the project is to analyse the advantages and disadvantages of introducing quota systems for waste to be landfilled and incinerated in Denmark. The project aims to evaluate possible quota models and identify and assess legal and institutional barriers. B 4.2.1 New initiativesContinued development of environmental cost-benefit analysis methods The numerous cost-benefit analyses in the area of waste management have shown that there is a need to develop the environment-economic method and create a more uniform base of calculation prices. Firstly, it is not currently possible to place a value on all parameters in such analyses, but often only for a few for which reliable valuation estimates exist. Secondly, there is often a not insignificant uncertainty linked to valuation of the individual parameters. Thirdly, there are a number of methodological problems associated with including effects in other countries in the traditional cost-benefit analysis. Much of the waste generation in a product's life cycle and raw material consumption often takes place in foreign countries today, and waste treatment is increasingly taking place abroad. It has therefore been found that analyses that only include domestic effects can lead to narrow conclusions. Ongoing efforts are therefore being made to refine and develop the method. This work is partly being done in the Danish Environmental Protection Agency and the National Environmental Research Institute, Denmark, and seeks to achieve greater cohesion between environment-economic analyses and life-cycle analyses, and to provide a more uniform base of calculation prices. Implementation of EU Directives The Strategy contains various types of initiatives. A number of measures have been made necessary by new or revised EU directives, and as such, implementation in Danish legislation is compulsory. The costs of these initiatives has been estimated:

In order to achieve the goal in the Packaging Directive, plastic packaging must be collected from households. On the basis of environmental cost-benefit analyses carried out, the collection method with the lowest costs per tonne of plastic waste has been chosen. The total costs are estimated to be approx. DKK 1.9 million per annum. In order to achieve the goal in the Packaging Directive, it will also be necessary to increase the collection of plastic transport packaging from enterprises that handle large quantities. This is not expected to lead to an increase in net expenses for enterprises. The mew material-specific goals in the Packaging Directive are only expected to lead to a limited increase in the costs of collecting metal packaging from households. Should it become necessary to collect plastic packaging from enterprises that handle only small quantities, this will lead to an increase in costs to these enterprises. A report for the Danish Folketing will be prepared in 2005 on how the goal of 55 per cent recycling of all packaging waste can be achieved. The other initiatives will be carried out in a way that ensures improved cost-effectiveness of environmental policies. To date, electrical and electronic products have been collected via municipal schemes financed through municipal charges. Under the new directive, producer responsibility will be introduced, with the result that waste management costs will be included in the prices of these products. Costs associated with the waste treatment of electrical and electronic products are expected to constitute 0.2 – 3 per cent of the products' purchase prices. The costs of treating animal waste have been estimated by industry to be approx. DKK 100 million per annum for incineration, and approx. DKK 100 million per annum for prior treatment – DKK 200 million in total. Incineration of meat-and-bone meal is exempt from waste tax. The increased costs to industry of managing the waste are due to the regulations in the Animal By-products Regulation and the resulting amendments to regulations made by the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries. The economic consequences of implementing the annex to the Directive on the landfill of waste are difficult to calculate. Before the waste is landfilled, information must be available on the composition of the waste and leaching of contaminants in the short and long-term ("characterisation"). The associated costs can only be calculated when it is known which types of waste must be characterised. The total costs to waste producers for characterisation of waste types for landfill are estimated to be of the order of DKK 100-200 million. It is expected that these costs will be incurred over approx. a two-year period (2004-2006). In addition to the costs of characterisation, waste producers will be regularly required to document that the particular waste type characteristics are not changing over time. This documentation will be in the form of analyses (compliance tests) aimed at showing whether the composition and leaching characteristics of a waste type have changed in relation to the results from the earlier characterisation. If the characteristics are changing, the waste producer may, in the worst case, be required to perform a new characterisation of the particular waste type. The total annual costs to waste producers for carrying out compliance tests are estimated to be in the order of DKK 5-10 million. In the 1990's, international rules were implemented regarding the phasing out of substances that deplete the ozone layer, in the Montreal Protocol and in an EC Regulation on substances that deplete the ozone layer. One study has shown that the greatest quantity of these substances is found in district heating pipes. The volume of decommissioned district heating pipes that contain ozone layer depleting substances will significantly increase in the years ahead, but no information is available on how many of these decommissioned pipes will be excavated. It will be necessary to investigate this before the expenses associated with separate treatment of district heating pipes containing ozone-depleting substances can be calculated. When a specific scheme is implemented for the waste management of these waste fractions, emphasis will be given to finding the most cost-effective scheme. The table below summarises the economic consequences of the Waste Strategy 2005-08, with expenses divided between the public and private sectors:

* The DKK 200 million for implementation of the Animal By-products Regulation are the result of regulation changes by the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries. Other initiatives in the Waste Strategy require further assessments of the economic consequences. No specific new initiatives will be implemented in these areas until a cost-benefit analysis has been carried out. A number of initiatives relating to the separation of special fractions were started as a result of the previous waste plan. In these areas, a decision on the final treatment of the fractions will await investigation of environmental and economic factors. This applies to initiatives such as:

These analyses are expected to be completed in 2003. A number of initiatives in the Waste Strategy indicate the direction the Government wishes to work towards. Measures under these initiatives will not be economically evaluated before the Strategy comes into force. However, the environmental and economic consequences will be evaluated before decisions are made about starting specific, binding initiatives. This may be relevant within initiatives such as:

In addition, a number of initiatives will require that elucidation projects be carried out with funding from the Danish Environmental Council for Cleaner Products. B.5 Experience from other countries in preventing wasteB.5.1 International waste prevention initiatives – OECD, EU and UNWaste prevention and improved resource efficiency need to be viewed from an international perspective. The large volumes of waste produced outside of Denmark in connection with the extraction and processing of raw materials do not appear in Danish waste statistics – this waste appears in the countries producing the raw materials, typically in developing countries. The import into Denmark of products and semi-finished goods from other European countries in particular also has great significance. Any waste prevention strategy that builds upon product-oriented initiatives must therefore be implemented at EU level. Examples of EU initiatives include the Flower eco-labelling scheme and work on standardisation in the European Standardisation Committee (CEN). Denmark is not alone in placing a high priority on waste prevention. Waste prevention has been an important element in waste policy in several OECD countries for many years. Since 1998, the OECD has targeted its waste minimisation efforts more specifically on waste prevention issues. In August 2000, the OECD published a comprehensive report on waste prevention: Strategic Waste Prevention - OECD Reference Manual. The OECD is also working on developing tools to evaluate the implementation of waste prevention, especially quantitative indicators. The Basel Convention is the only international regulation of waste at global level. The main purpose of the Convention is to regulate transboundary transport of hazardous waste, but over the last few years the Convention has shifted focus towards waste prevention, waste minimisation, and environmentally responsible waste treatment. In December 2002, it was decided to implement a strategy focusing on these new areas. More specifically, a number of projects will be initiated with the aim of ensuring global waste prevention. The Community Strategy for Waste Management states that "the key objective of any Community waste policy based on the precautionary and preventive principle must be to prevent the generation of waste. The Commission believes that in any case waste prevention must be considered preferable to any other possible solution." The Commission aims to promote waste prevention via initiatives in the following areas: Continued promotion of the development and use of cleaner technology, improvements to the environmental aspects of technical standards, promotion of the use of economic instruments in the waste sector, promotion of environmental revision plans for economic players, and promotion of waste-saving products through eco-labelling. The Commission also aims to promote consumer information in this area and hence contribute to changing consumption patterns. The Council Resolution on the Community Strategy for Waste Management clearly supports giving highest priority to waste prevention and devoting greater efforts to this area. Prevention of packaging waste formally has the highest priority in the Packaging Directive. The Directive lays down a number of "essential requirements" relating to the production and composition of packaging, including the fact that packaging volume and weight must be reduced to the essential minimum. The aim is for these requirements to be clarified in harmonised European standards prepared by CEN. In 2001, the Commission published a standard on prevention. The Sixth Environmental Action Programme for the European Community contains goals and priority areas for initiatives for the sustainable use and management of natural resources and waste. One goal is to achieve a significant general reduction in volumes of waste through waste preventive initiatives, better resource utilisation and a change to more sustainable production and consumption patterns. It is therefore a high priority to prepare a thematic EU strategy for the sustainable use and management of resources. This strategy will contain analyses of material flows, and goals for resource efficiency and reduced resource consumption, development of technology and the use of market-based and economic instruments. Waste prevention initiatives will also be developed and implemented, including the development of quantitative and qualitative goals for the reduction of all relevant waste types in 2010. According to the programme, the Commission is also going to prepare a strategy for waste recycling. At the UN Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002, a decision was made to develop a 10-year framework for programmes to support national and regional initiatives for sustainable production and consumption. Efforts should be made within the EU to link this 10-year framework to the EU strategy for the sustainable use and management of resources. B.5.2 Waste prevention in other countries – Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands and AustriaA number of countries have set specific goals for waste prevention: In 1999, Norway set a goal to the effect that developments in the generated volume of waste must be significantly lower than in economic growth. This goal is to be achieved through a number of different measures:

The Committee for Waste Reduction submitted a public report [12] to the Norwegian Ministry of the Environment on 7 November 2002. The figure below summarises the report's proposals for measures and initiatives and the connections between them.

The report also states five primary points for achieving waste prevention and recovery: "To achieve long-term waste prevention, the supply of materials from nature to the technosphere must be reduced. This can be realised by:

Waste prevention also involves:

The first point requires changes to the basic forces in our economy through a permanent change in the preferences of the population. The other points are more organisational or technical in nature." Sweden has set the long-term goal of reducing the volume of waste for landfill (excluding mining waste) by 50-70 per cent between 1994 and 2005. In "Sweden's environmental goals – the responsibility of our generation" from 1999, waste prevention is discussed under the goal of a well-developed environment. The report states that the total volume of waste and the hazard from waste must be reduced. No actual quantitative targets have been set. In the Swedish strategy for waste management [13] the following guidelines have been established for more efficient and sustainable resource usage:

The strategy does not contain more precise measures to achieve resource efficiency, apart from mentioning producer responsibility as an important factor, and the recycling of resources in waste is emphasised. In 1988, the Netherlands prepared a "Memorandum for waste", setting goals for 29 high-priority flows of waste. These goals aim to reduce the hazardousness and volume of waste by 5 per cent in 2000 compared to levels in 1986. Quantitative goals for absolute waste prevention were subsequently set in the first two Dutch national environment policy plans, NEPP and NEPP2. However, in the latest plan, NEPP3 from 1998, no quantitative goals have been set for waste prevention. In 2002, the Dutch Ministry of the Environment submitted a draft national waste management plan [14] for public hearing. This plan focuses on prevention and limiting the environmental impact from waste by reducing the volume of waste landfilled and incinerated. The goals in the national waste management plan directed towards prevention are as follows:

The goal is to limit growth in volumes of waste to a total of 16 per cent for the period 2000-2012. This needs to be seen in the context of expected economic growth over the same 12-year period of 38 per cent. To achieve this goal, the existing waste prevention policy needs to be maintained, and supplemented and intensified for a number of specific waste types. Initiatives need to be targeted towards large flows of waste with potential for prevention – especially industrial waste – and towards flows of waste with a high landfill or incineration rate – especially residual waste from households, and trade, service and the authorities. A number of measures for achieving these goals are mentioned:

Austria issued a national waste management plan in June 2001. The plan contains measures for more efficient waste prevention and recovery, primarily aimed at the production sector. The following solutions are proposed:

The plan identifies the following measures that can be employed:

The Austrian Ministry for Life has appointed work groups with representatives from the financial, scientific and administrative sectors to describe and quantify the potential for waste prevention and recovery of waste from various industrial sectors in Austria. Footnotes[1] {0>ISAG – Informations System for Affald og Genanvendelse.<}0{>ISAG – Information System for Waste and Recycling.<0} [2] Constant prices are prices for the year, adjusted for inflation, and are thus an indicator of real growth [3] The initiatives in this Strategy are not included in the forecast.<0} [4] In accordance with the Statutory Order on Waste, no. 619 of 27 June 2000.<0} [5] Annual material flow analyses are carried out for cardboard, paper, plastic packaging, glass packaging, metal packaging, and organic waste.<0} [6] The assumptions and statistical bases for calculating the new waste indicators are described in detail in the report: Danish Environmental Protection Agency 2003, "Resource savings in waste treatment in Denmark" [7] This excludes a small quantity subject to special treatment or placed temporarily in storage. [8] Briefing from the Danish Environmental Protection Agency, no. 2, 2002.<0} [9] 2001 figure for normal waste suitable for incineration weighted by volume [10] 2001 figure for sorted, waste not suitable for incineration for landfilling, weighted by volume [11] 1999 figure. European Environment Agency – Environmental assessment report No. 2. [12] Norway's Public Reports, NOU 2002: 19 "Avfallsforebygging, en visjon om livskvalitet, forbrukerbevissthet og kretsløpstenkning" " http://odin.dep.no/md/norsk/publ/utredninger/nou/022001-020007/index-dok000-b-n-a.html [13] The Swedish Government report 1998/99:63 "En nationell strategi för avfallshanteringen" of 4 March 1999 [14] Ministry of Housing, Planning and the Environment: Draft National Waste Management Plan, the Netherlands 2002-2012, 11 January 2002, Public enquiry version

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||