|

Waste Strategy 2005-08Contents1 Waste Strategy 2005-2008, focus areas

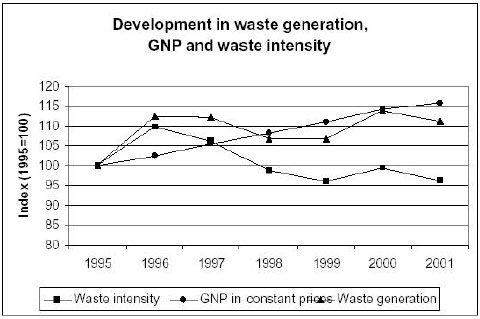

2 Focus on preventing loss of resources and environmental impact from waste

ForewordA healthy and sustainable environment is the overarching framework of all the government's environmental initiatives. We will therefore not accept unnecessary impacts on the environment from our waste. This is the clear message in Waste Strategy 2005-08 – the Government's waste policy for the next four years. The way ahead in waste management is to reduce the loss of resources and the environmental impact from waste. It is vital that waste be managed in the way that represents the best value – both in terms of the environment and economics. As a completely new initiative, this Strategy provides the first calculations for a number of waste indicators that show how much waste is impacting on the environment. If we combine these waste indicators with economic analyses, we will obtain a better and more thorough basis for evaluating whether waste is being managed correctly. Waste Strategy 2005-08 sets clear goals for what we hope to achieve in waste management over the next four years. One goal is to make the environmental improvements resulting from the money invested visible. And we will work towards making the waste management sector as efficient as possible. Another great challenge is to decouple growth in the volume of waste from economic growth in society. We are currently already recycling large volumes of waste. And that is a good thing. But there remain areas where we could do better. In particular, waste from industry and the service sector will be closely examined – as there is still more waste that could be constructively recycled in these areas. This Strategy will equip Denmark to make a positive contribution to future waste management initiatives in the EU. I see Waste Strategy 2005-08 as marking the beginning of a Danish waste policy that focuses on the environment, efficiency and economics, to the benefit of sustainable development. Let me encourage everyone to participate actively in implementing the Government's policy. We all have a responsibility to create the best conditions for a healthy and sustainable environment. And the way to achieve this is by having a constructive waste policy, as this Strategy describes. Hans Christian Schmidt Guide to the PlanChapters 1 to 3 contain a general description of the Strategy and initiatives of the plan. CHAPTER 1 presents the main elements of the waste management plan. CHAPTER 2 shows the development in the volume of waste up until 2001, and introduces the new focus on prevention of the loss of resources and environmental impact from waste. New initiatives to prevent waste are also discussed. CHAPTER 3 summarises all the planned initiatives relating to waste prevention, increased recycling, reduced resource consumption, improved quality of recycling/treatment, and reduced landfilling. These initiatives will be implemented in the years 2005-2008. Initiatives are presented for all waste sectors, and specific fractions are mentioned for the most relevant sectors. These chapters are followed by five appendices examining the individual issues. The Waste Management Plan - and especially the appendices - have been designed to be used for reference. As a result, some material may be repeated. APPENDIX A, on waste regulation, contains a review of the Danish instruments used in the area of waste management. EU waste regulation is also discussed. APPENDIX B discusses the statistics for waste volumes and technological development. New initiatives to improve statistics in the area of waste management and the need for technological development are presented. The costs and environmental effects of waste management, and experience from other countries with waste prevention are also discussed. APPENDIX C, on capacity, contains a review of capacity at waste incineration plants, landfill sites, and treatment plants for hazardous waste. In APPENDICES D and E, each sector and fraction is reviewed: Status for 2001, aims for 2008, initiatives to meet goals, current regulation in the area, environmental and economic evaluation of initiatives, and the plan's implications for national and municipal waste authorities. Treatment capacity for each fraction is also discussed. 1 Waste Strategy 2005-2008,

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sector | Waste prevention initiative |

| Households |

•Information campaigns with specific recommendations for waste prevention •Educational material on resource consumption and waste prevention for schools and child-care centres •Establish or improve municipal re-use schemes |

| Trade and service |

•Motivate the trade and repair sectors to make greater use of reusable transport packaging •Continue the work in the product panel for retail trade |

| Industry |

•Re-use large plastic containers •Limit consumer production waste due to inappropriate packaging •Guidelines on using the conditions on prevention of waste. These guidelines must be based, in particular, on the European Commission's BAT notes (see Appendix D5) •Tools to use in connection with the analysis and reduction of an enterprise's waste generation and management |

| Building and construction |

•Guide on waste prevention for use during property renovation |

It is currently very difficult to calculate the environmental effect of these preventative initiatives, as no empirical data is available for changes in the behaviour of the population and trade and industry. However, an attempt will be made to evaluate the environmental effects and the total socio-economic consequences of these preventative initiatives.

2.3 New indicators for loss of resources and environmental impact

New waste indicators have been developed and calculated for loss of resources and landfill requirements for 22 materials present in waste. These indicators express the environmental benefit associated with moving a particular waste fraction from landfill to recycling or incineration. This means that for each material type, the loss of resources and energy associated with landfilling the entire fraction is calculated, and compared with a new treatment situation in which a realistic quantity is either recycled or incinerated [5]. These indicators are calculated on the basis of the volume of waste in 2000, and no forecasts have been made for the future volume of waste.

These indicators can be used to prioritise environmentally initiatives within each fraction, since they tell us whether anything can be gained in terms of resources or the environment from recycling or incinerating the waste. In this way, the new indicators can be used to select where we achieve the minimum environmental impact. And as mentioned in chapter 1, the indicators provide an important foundation when we have to calculate the quality of waste treatment.

Armed with these new indicators, we will be able to select specific areas upon which to focus our future initiatives. We have now calculated these indicators for the first time, and this information can provide a basis for new initiatives. But it is important to mention that before these specific initiatives are implemented, a more thorough environmental and economic analysis of the measures will be carried out.

The new indicators require a very large LCA statistical base, analysis of material flows and complicated calculations, and are therefore associated with a certain degree of uncertainty. The method and statistical base have been critically reviewed and it has been concluded that the indicators undoubtedly provide a more accurate picture of the real environmental impacts than is the case for existing indicators, based exclusively on the volume of waste. However, the indicator for landfill requirements is extremely uncertain.

Due to a lack of LCA data, it has not been possible to calculate the indicators for all waste fractions. Neither do the indicators include calculations of toxic effects, since statistics in this area do not exist. It is therefore vital that the indicators are supplemented with a qualitative assessment of hazardous emissions from the processes in each material's life cycle before the final decisions about new initiatives are made.

New treatment methods have been developed for the environmentally harmful PVC and impregnated wood fractions. However, LCA data is not available for these processes, so these methods have not been included in the calculation of the indicators.

2.3.1 Definitions

For each of the selected materials, three indicators have been calculated:

- Resource consumption

- Energy consumption

- Landfilling requirements

Resource consumption is expressed in person-reserves. A person-reserve is the amount of the resource available per person. (For non-renewable resources, the available amount is calculated per world citizen, but for renewable resources, the available amount is calculated per person in the region).

Energy consumption is calculated in person equivalents. A person equivalent corresponds to the amount of energy (primary energy) a Danish resident uses in a year.

Landfilling requirements are also expressed in person equivalents. In this context, a person equivalent is the amount of landfill generated per Danish resident, per annum.

2.3.2 Materials and forms of treatment

The indicators are based on the volume of waste from 2000, and the treatment being employed that year. The volume of waste that was landfilled, incinerated, recycled and re-used (if any) is shown in figure 2.a.

Click here to see the Figure.Figure 2.a. The volumes of material treated, divided by form of treatment and material (tonnes).

Sludge is specified as 20% dry matter content.

As the figure shows, we landfill quite large quantities of paper and cardboard, impregnated wood and plaster. Paper and cardboard, wood, organic domestic waste and the many contributions from various plastic materials comprise the largest quantities incinerated. The largest quantities being recycled are concrete, tiles, asphalt (incl. re-use), paper and cardboard, and iron and steel.

2.3.3Indicators for resource savings

Click here to see the Figure.Figure 2.b. Resource savings achieved based on the existing waste treatment for the various materials, calculated in PR (person-reserves).

Figure 2.b. shows how many resources we have saved based on the existing treatment of waste, compared to the situation if all waste was landfilled. These resource savings are divided into energy resources and other resources.

In particular, recycling metals has led to the greatest contribution to the resource savings already achieved.

Lead, tin and zinc are not shown in the figures, since the necessary LCA data is not available to calculate these indicators. But it is estimated that the resource savings for lead, zinc, and tin would be at the same level as those for the other metals, since these resources have a relatively short supply horizon.

Paper, wood, and the six plastic fractions contribute particularly to energy resource savings, since incineration of these replaces energy raw materials used for electricity and heat production.

The building materials – concrete, tiles and asphalt – are not shown on the figure, since no significant resource savings are achieved through recycling. This is because concrete, tiles and asphalt replace resources that exist in abundant quantities.

Click here to see the Figure.Figure 2.c. Potential for further savings in resource consumption for the various materials, calculated in PR (person-reserves).

Figure 2.c shows how much room there is for improvement, for example, if we were able to recycle a large proportion of a fraction which is currently being incinerated or landfilled. Thus we have an indicator value that shows how many more resources can be saved by improving the existing treatment.

A positive value indicates that an environmental benefit can be achieved if we can save resources by moving from the existing waste treatment to an "optimised waste treatment" with increased recycling. As part of the calculation, an assessment was made as to how much more it would be realistic to recycle.

For paper, plastic (excluding PVC), aluminium and copper, figure 2.c shows that there is the potential for significant resource savings by increasing recycling. For wood, resource savings can be achieved by increasing incineration in waste incineration plants.

The figure also shows that we cannot save further resources by recycling greater quantities of organic domestic waste, automobile rubber and oil than is currently the case.

For PVC, it is assumed that a larger proportion of PVC waste will be landfilled for environmental reasons, leading to negative savings in energy resources.

2.3.4 Indicators for resource savings

Click here to see the Figure.Figure 2.d shows how much energy we have saved based on the existing treatment of waste, compared to the situation if all waste were landfilled.

Figure 2.d. Energy savings achieved based on the existing waste treatment for the various materials, calculated in PE (person equivalents).

This figure shows that we have already saved a significant amount of energy through treatment of most of the materials suitable for incineration. This reflects the fact that incineration with energy recovery is a significant element in existing waste management. In particular, the last ten years of expansion using power generating waste incineration plants has contributed significantly to the energy savings achieved. Generating power at waste incineration plants replaces natural gas and other fossil fuels with waste.

Click here to see the Figure.Figure 2.e. Potential for further savings in energy consumption for the various materials, calculated in PE (person equivalents).

Figure 2.e shows how much more energy we can save, for example, if we were able to recycle a large proportion of a fraction which is currently incinerated or landfilled. Thus we have an indicator value that shows how much more energy consumption can be saved by improving the existing treatment.

Figure 2.e shows that further energy resources can be derived from our waste. In other words, we can save energy resources by increasing recycling of waste fractions compared to current levels. However, this is not the case for organic domestic waste, PVC and automobile rubber.

If we are to save more energy resources, we must focus on increasing the recycling of aluminium and paper. For most plastic materials and for glass packaging, modest energy savings can be achieved by increasing recycling as opposed to incineration. The big potential for further energy savings for wood is due to the assumption of an increase in incineration as opposed to landfill.

2.3.5 Indicators for landfill requirements

The indicator values for landfill requirements are extremely uncertain.

Click here to see the Figure.Figure 2.f. Savings in landfill requirements achieved based on the existing waste treatment for the various materials, calculated in 10PE (person equivalents).

Figure 2.f shows how much we have reduced our landfill requirements based on the treatment of waste in 2000, compared to the situation if all waste was landfilled.

The indicator values for saved landfill requirements show that the existing waste management is ensuring that large quantities of waste are not ending up at landfill sites.

The indicator also incorporates the "hidden material flows", wherever this has been possible. The hidden material flows are included in data for coal extraction, and partially in data for metal extraction. Landfilled waste will thus be included in connection with the extraction of new materials or energy to replace materials lost through landfilling or incineration.

For most metals, there are significant landfill requirements in connection with the extraction of ore. However, due to the lack of data for these hidden streams, they are generally not included in the calculations. If the hidden streams were incorporated everywhere, increased recycling would lead to significant savings in landfill requirements for most metals.

Click here to see the Figure.Figure 2.g. Potential for further savings in landfill requirements for the various materials, calculated in 10PE (person equivalents).

Figure 2.g shows how much more we can save in landfill requirements, for example, if we were able to recycle a larger proportion of a fraction which is currently incinerated or landfilled. Thus we have an indicator value that shows how much more can be saved in landfill requirements by improving the existing treatment.

For glass and aluminium, there is a significant potential to save landfilling as glass that is not recycled is incinerated, generating slag requiring landfill. Similarly, aluminium does not burn in the thicknesses that are typically found in household waste, and hence contributes to the slag volume.

For several materials, an increase in landfill requirements can be seen. For concrete, tiles and PVC, the increased landfill volumes are due to allowance for requirements for increased sorting of contaminated materials for landfill, compared to the situation in 2000. There has been a shift here from recycling to landfilling.

The results must be interpreted with care, as the indicators are derived from many different types of waste, without weighing up the degree of environmental hazard associated with these types of waste.

2.3.6 Summary of the new indicators

With the existing waste management, involving 66% recycling, 24% incineration, and 10% landfilling, significant savings in resource consumption have been achieved for waste from paper and cardboard, wood, and these metals: aluminium, iron and steel, and copper. Significant energy savings have been achieved through the existing waste treatment of paper and cardboard, wood, PE plastic, aluminium, and iron and steel. There have been savings in landfill requirements under the existing waste management for the majority of waste fractions, except for impregnated wood, PVC and plane glass.

The most important potential for further savings in both resource consumption and energy consumption is found in the metals, paper, and plastic – excluding PVC. The greatest potential for further savings in landfill requirements is found for glass packaging and aluminium.

2.3.7 Conclusion

The development and calculation of the new indicators has marked the beginning of a valuable process. We are gaining greater and more detailed knowledge about the environmental impact of waste. These indicators are contributing to providing a better foundation for making the right decisions in waste management.

We are only at the beginning of this process, and it will be many years before we have a well-developed and complete tool to use in prioritising initiatives. But we have taken the first step in developing the right tool to ensure that we achieve better quality in our waste management. If we use the indicators and the other knowledge in this area together with cost-benefit calculations, we will be well on the way to having a tool that tells us where we can gain improved cost-effectiveness from environmental policies.

During the years ahead we need to develop new indicators for further environmental effects, and to improve our statistical base. We must regularly update the indicators we have already calculated to get an overview of whether we are sending waste to the treatment process that is most beneficial for the environment.

3 Initiatives

- 3.1 General focus areas

- 3.2 Sectors and fractions

- 3.3 Waste incineration plants

- 3.4 Building and construction

- 3.5 Landfill sites

- 3.6 Households

- 3.7 Industry

- 3.8 Institutions, trade and offices

- 3.9 Power plants

- 3.10 Public wastewater treatment plants

The Danish Waste Strategy focuses on prevention of resource consumption and environmental impacts from waste.

Future initiatives will not be based purely on the volume of waste alone. The total resource consumption and environmental impact from waste treatment will be central elements in the evaluation of future initiatives.

Waste prevention, increased recycling, reduced landfilling and improvements to the quality of waste treatment will continue to be important areas, and initiatives to tackle xenobiotic substances in waste must continue to be enhanced.

For Waste Strategy 2005-2008 to succeed, a number of initiatives must be commenced at various levels. Some initiatives are of a more general nature, while others will be adapted to different sectors or directed at the waste fraction in question.

The Strategy contains more than 100 new initiatives, covering the entire waste management spectrum. The majority of these initiatives are directed towards implementing EU and Danish regulations, and making new knowledge available through development and elucidation projects. The Strategy also contains a number of initiatives that aim to develop new tools, sub-strategies, environmental and cost-benefit assessments, and a small number of information activities.

Waste can be divided according to the source (sector) generating it. These sectors are waste incineration plants, building and construction, households, industry, institutions, trade and offices, power plants, and wastewater treatment plants. Landfill sites are also considered to be a sector. The total volume of waste is distributed as follows: the building and construction sector 26%, households 24%, industry 21%, institutions/trade and offices 10%, and power plants 10%. Wastewater treatment plants contribute 9% of waste.

Residues from waste incineration plants are not included in the total volume of waste in the figure, as they would otherwise be counted twice.

The Waste Strategy initiatives are described briefly below. The first initiatives are of a more general nature, followed by a number of initiatives divided according to the various waste source sectors. A more detailed description of initiatives is given in Appendices A to E.

For each sector, total aims have been calculated for recycling, incineration and landfilling arising as a consequence of the initiatives taken in relation to each waste fraction.

3.1 General focus areas

Statistical base

There is a need to continue the systematic collection of comparable data on waste generation and treatment in a way that permits both enterprises, and local and national authorities, to use it. It is also important to measure the effect of future initiatives in the area of waste management. Initiatives to improve the statistical base for the entire waste sector are described in Appendix B on waste data.

In 2002, the Minister for the Environment appointed a work group to examine the organisation of waste management. One of the group's tasks was to look at registration and reporting requirements, with the aim of simplifying these. Early in the plan period, a model for a central register for waste carriers will be developed.

Indicators for resource consumption, energy consumption and landfill requirements

The new waste indicators for resource consumption, energy consumption, and landfill requirements must be refined, and attempts must be made to obtain further life-cycle analysis data (LCA data) for the calculations. In order to be able to monitor the trends, the waste indicators should be recalculated regularly, every two or three years. There is a great need in the future to supplement the LCA databases with data for recycling processes, and especially for human and ecotoxic effects. Further LCA-based indicators should be developed, if the statistical base allows this. The waste indicators will provide an improved foundation for selecting the best environmental initiatives in the future.

The final choice of treatment methods will be based on the indicators, together with other knowledge about the environmental impacts of waste, and cost-benefit analyses. Together, these initiatives provide a good prioritisation tool for selecting specific treatment methods for the individual waste fractions.

Knowledge-sharing

Knowledge-sharing is a central instrument to be used by the players in implementing the Strategy. Information can support and contribute to fulfilling the various elements of the Waste Strategy. Relevant information must be made available to the players via the Internet and other media. Waste Centre Denmark has a central role in this area.

Waste prevention

In Waste Strategy 2005-08, it has been decided to implement waste prevention measures initially where the barriers are small and where results can be achieved in the short term. Initiatives will be commenced in four sectors: households, the service sector, industry, and building and construction.

Technology development

Better quality in waste treatment requires the development of new technologies. There are several barriers that prevent this development taking place automatically. An example of a barrier is the fact that there is no security that the necessary volumes of waste will be supplied to the treatment plants (see Appendix B on technological development).

If technologies adapted to future waste are to be developed at a general level, it is necessary to continue to support the development of new technologies. Furthermore, central requirements must be placed on waste treatment when technologies exist. This can contribute to treatment plants being established and operated under market conditions.

Transparency in municipal fees

Transparency needs to be achieved in municipal fees. Changes to the legal basis for fees in the Environmental Protection Act will be proposed during parliamentary session 2004-05. In addition to transparency, the following factors will be considered when selecting the formulation of the legal basis for fees: the municipalities' need for flexibility in waste management, the rule of law, the polluter pays principle, and environmental, economic and legal efficiency.

Organisation of waste management

In spring 2002, the Government appointed a work group to undertake a complete assessment of the scope and significance of the most important problems in the area of waste management. At the end of 2004, the work group will offer proposals for future solutions within areas where it considers that changes to organisation and legislation have been found to be necessary.

The Waste Strategy should therefore not be considered to be an exhaustive description of the initiatives that will be implemented during the period in relation to the organisation of waste management and the use of control mechanisms. Rather, the Strategy will be supplemented by new initiatives when the Government has evaluated the recommendations of the work group.

Municipal regulations

The number of municipal regulations must be reduced, and the contents of regulations must be harmonised to make it easier to work out which rules apply in each municipality and to compare municipalities.

Taxes

Investigation will be made into whether waste tax rates support environmental priorities in the area of waste management. At the same time, assessment should be made of whether the waste tax can be used as a more precise control instrument, for example, in connection with the industrial use of residues from sludge incineration and shredder waste. A change in the waste tax will not lead to a total increase in yield from the tax.

Capacity, general

In most areas, the market generates the necessary capacity for the treatment of waste. This is especially true for waste recycling. One of the areas where it has not yet been possible to establish the necessary capacity is sites for landfilling acidic flue gas cleaning products.

Incineration and landfilling are special areas where deregulation is being discussed. Currently, the capacity of incineration plants and landfill sites is largely controlled by the national and municipal authorities. If these parts of the waste management sector were deregulated, government control of this capacity will disappear. The advantages and disadvantages of potential deregulation of the waste management sector are being considered by the work group on the organisation of the waste sector. This group is considering how the necessary capacity can be ensured.

Capacity at waste incineration plants

Currently, challenges relating to changes in capacity requirements, overall energy policy, and stricter environmental requirements are solved in close co-operation between municipalities, counties and national authorities.

It is believed that the planned expansions will provide sufficient capacity to meet incineration requirements in 2008.

The objective is to match incineration capacity to actual requirements and locate it in areas where the best possible energy utilisation and greatest possible CO2 mitigation are obtained, taking into consideration the principle of regional self-sufficiency.

Much incineration capacity is currently based purely on hot water generation. It is estimated that after 2004 there will still be a need to utilise capacity in several of these incinerators. However, these incinerators are being gradually phased out as new incinerators are built, and in 2008, approx. 95% of waste for incineration is expected to be processed in CHP incinerators that produce both heat and power.

Landfill capacity

Up until 2008, landfill capacity will be sufficient at the national level, but there are large regional differences due to varying degrees of difficulty in finding suitable sites for placing landfill. In addition, experience has shown that planning should be carried out with a 12-year horizon. Capacity planning should therefore look further ahead than the four years that are typical practice in planning, and should be carried out in cooperation between counties and municipalities.

Hazardous waste

A strategy for hazardous waste will be prepared. The purpose of this strategy will be to identify whether the various regulations relating to hazardous waste represent barriers to the best economic and environmental management of waste, and to identify potential initiatives to minimise these barriers.

3.2 Sectors and fractions

Initiatives for each sector are described below. Each sector description will contain details of how individual objectives will be achieved, including which fractions will be the focus of initiatives (see also Appendix D on sectors, and Appendix E on fractions).

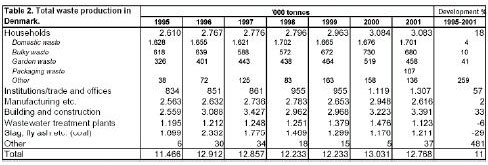

The table below contains an overview of actual waste treatment in 2001, based on the latest waste statistics, and an overview of the Waste Strategy's aims for 2008.

| Actual waste treatment 2001 | Waste Strategy – aims for 2008 | |||||

| Recycling | Incineration | Landfilling | Recycling | Incineration | Landfilling | |

| Household waste Domestic waste Bulky waste Garden waste |

29% 16% 18% 99% |

61% 81% 49% 0% |

8% 3% 26% 1% |

33% 20% 25% 95% |

60% 80% 50% 5% |

7% 0% 25% 0% |

| Waste from institutions, trade and offices | 36% | 49% | 12% | 50% | 45% | 5% |

| Industry | 65% | 12% | 22% | 65% | 20% | 15% |

| Building and construction | 90% | 2% | 8% | 90% | 2% | 8% |

| Sewage works | 67% | 27% | 6% | 50% | 45% | 5% |

| Power plants | 99% | 0% | 1% | 90% | - | 10% |

| Total | 63% | 25% | 10% | 65% | 26% | 9% |

Where the sum of recycling, incineration and landfilling components does not amount to 100% in the table, this is because a small proportion of waste is put in temporary storage.

3.3 Waste incineration plants

Aims for 2008

- 85 % recycling of slag from incineration plants

- a Danish solution for the management of flue gas cleaning products

In 2001, approx. 540,000 tonnes of residues (slag and flue gas cleaning waste) were generated at waste incineration plants [6]. It is expected that increasing amounts of waste will be incinerated in the years ahead, leading to increasing amounts of residues being generated.

In future, fractions that can be recycled or that cause environmental problems must be prevented from reaching waste incineration plants.

Residue quality must be improved. Residue recycling and landfilling must also give maximum consideration to the protection of groundwater resources. This will require new treatment methods to be developed, for example, for flue gas cleaning waste.

Waste incineration plants, initiatives

| Electrical and electronic products | The EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment has to be implemented by the end of 2004 |

| Flue gas cleaning waste | An action plan for a permanent solution for the management of flue gas cleaning products generated in Denmark will be prepared. |

| Slag | The Statutory Order on the Recycling of Residues and Soil for building and

construction purposes will be extended to contain limit values for organic substances Leaching of xenobiotic substances from slag must be reduced. Investigation will be made into whether there should be a requirement to sort fractions with particularly high heavy metal content from the remaining slag. |

Electrical and electronic products must be collected separately and managed in a more environmentally sound manner. Requirements for their management were laid down in a Statutory Order issued in 1998. The new EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment must be implemented in Danish legislation by the end of 2004. Implementation of this directive will mean changes to requirements, and that more products will be subject to separate treatment.

Flue gas cleaning waste is classified as hazardous waste [7]. This waste used to be landfilled temporarily or exported, as no suitable methods to stabilise it were available. On the basis of an environmental and cost-benefit analysis, and in cooperation with waste incineration plants, an action plan will be prepared for the future management of flue gas cleaning products generated in Denmark. This action plan will contain deadlines for when each problem with flue gas cleaning products has to be solved. Once environmentally responsible reprocessing methods have been established, specific rules will be laid down for the management of flue gas cleaning products from waste incineration plants.

In 2001, 87% of slag [8] was recycled. Future recycling of slag must continue to give maximum consideration to the protection of groundwater resources. The Statutory Order on the recycling of residues and soil for building and construction purposes will be extended to contain limit values for organic substances.

Recycling of slag from waste incineration must be increased by reducing the leaching of xenobiotic substances from the slag. This can be achieved by improved source separation of waste going to incineration or by sorting fractions with particularly high heavy metal content from the remaining slag.

3.4 Building and construction

Aims for 2008

- 90% recycling of building and construction waste

- recycling of building and construction waste gives maximum consideration to groundwater resources

- recycling of residues in the building and construction sector gives maximum consideration to groundwater resources

- indicators are used that make it possible to evaluate environmental initiatives in construction

The building and construction sector is characterised by a very high recycling rate for the waste generated. This high rate will be maintained, as waste recycling saves important resources.

The aim for 2008 is to maintain this high recycling rate. It must also be ensured that building and construction waste recycling gives consideration to the protection of groundwater resources.

In 2001, building and construction waste amounted to approx. 3.4 million tonnes. The volume of building and construction waste has been increasing over the last ten years.

Using funding from the Danish Environmental Council for Cleaner Products, a Construction Panel has been appointed which has prepared an action plan for sustainable construction.

Cross-cutting initiatives

During the next few years, a guide to waste prevention will be prepared. During the renovation of older properties, it is constructive to re-use previously used building elements. The guide will describe the activities that should be carried out during demolition to ensure the optimal re-use of building components. Renovation is an alternative to new construction, and the scope of property renovation compared to demolition therefore needs to be analysed.

Such high levels of contaminants have been recorded in building and construction waste that a nationwide investigation needs to be carried out to determine which contaminants are present and in what concentrations. The sources of these contaminants must also be identified.

An investigation will be carried out to describe the normal procedure for managing building and construction waste in the municipalities. For example, this investigation will clarify whether the individual fractions are mixed together before they are recycled, and whether the mixed fractions are recycled with the necessary Section 19 permission or Chapter 5 environmental approval under the Environmental Protection Act.

It will be investigated whether there are environmental and health effects in connection with the use, renovation and demolition of buildings containing PCB.

Building and construction waste has sometimes been found to contain contaminants and should be treated like other residues. Consideration will be given to whether the recycling of building and construction waste should be regulated under the Statutory Order on residues and soil for building and construction purposes, in the long term. The necessary basis for revising the Statutory Order to also cover building and construction waste needs to be provided. It is expected that the Statutory Order will be extended to include fractions containing organic contaminants.

A proposal will be made for specific resource and environment indicators for individual construction projects. These indicators will enable building contractors to take responsibility for improving environmental factors in construction. Principles will also be proposed for a benchmarking system that makes it possible to evaluate environmental initiatives.

A project will be initiated to provide an overview of where environmental considerations should be incorporated into the existing legal and regulatory base. The existing requirements need to be assessed to determine whether they support the environment goals presented in the Construction Panel's action plan.

Focus needs to be given to the use of chemicals in buildings and building products. An investigation will therefore be initiated with the aim of developing a simple tool to evaluate and prioritise the use of chemicals in the building sector.

Building and construction sector, initiatives

| Cross-cutting | A guide to the prevention of building and construction waste will be prepared

An analysis of contaminants in building and construction waste will be carried out An investigation will be carried out that describes the procedure for managing building and construction waste The environmental and health effects of PCB in buildings will be investigated The Statutory Order on residues and soil for building and construction purposes will be extended to also cover building and construction waste and organic contaminants Proposals will be made for specific indicators for individual construction projects An overview will be provided of where environmental considerations should be incorporated into the existing legal and regulatory base. Focus needs to be given to the use of chemicals in buildings and building products |

| Asphalt | Asphalt recycling must be done in a responsible manner, taking into account environmental and health impacts. |

| Concrete | There must continue to be a high rate of concrete recycling, in an environmentally responsible manner. |

| Electrical and electronic products | The EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment must be implemented by the end of 2004 |

| Hazardous waste | A strategy for hazardous waste will be prepared

Criteria for environmental hazards will be implemented New treatment methods for hazardous waste fractions will be developed Information on hazardous waste regulations will be communicated |

| Mineral wool | The potential for recycling mineral wool will be investigated, including the development of recycling methods and of the market for recyclable mineral wool |

| Impregnated wood | Impregnated wood containing chromium, copper and arsenic-containing substances will continue to be treated as non-incinerable waste, and landfilled. Once better treatment methods have been developed, impregnated wood will be collected separately, if this is assessed to be environmentally and cost-effective. |

| Ozone layer depleting substances in waste fractions | Under the EU Regulation on ozone layer depleting substances, regulations must be implemented regarding the separate treatment, wherever possible, of products containing ozone layer depleting substances. This will apply to pre-insulated district heating pipes in particular |

| Plastic packaging | Under the Packaging Directive, 22.5% of plastic packaging must be recycled in 2008 |

| PVC | PVC waste must continue to be separated, either for recycling or landfilling. Once better treatment methods have been developed, PVC will be collected separately, if this is assessed to be environmentally and cost-effective |

| PCB and PCT | Evaluation will be made as to whether health impacts arise in connection with the use, renovation or demolition of buildings containing PCB |

| Residues from power plants, waste incineration plants and soil | Guidelines on the recycling and relocation of soil and residues will be prepared

The Statutory Order on recycling of residues and soil for building and construction purposes will be revised to also cover soil contaminated with

organic compounds |

| Tiles | Efforts will be made to ensure that tiles are recycled in an environmentally responsible manner |

| Wooden packaging | Under the Packaging Directive, 15% of wooden packaging must be recycled in 2008 |

Asphalt recycling must be done in a responsible manner, taking into account environmental and health impacts. The first step is to ensure that the health risk associated with laying crushed asphalt is minimised. This can be achieved by requiring asphalt to be compressed or compacted after laying, to limit dust emission. In the longer term, asphalt recycling will be covered by the Statutory Order on recycling of residues and soil for building and construction purposes.

There must continue to be a high rate of concrete recycling, in an environmentally responsible manner. In the longer term, regulations governing the management of concrete will be covered by the Statutory Order on recycling of residues and soil for building and construction purposes.

Electrical and electronic products must be collected separately and managed in a more environmentally sound manner. Requirements for their management were laid down in a Statutory Order issued in 1998. The new EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment has to be implemented in Danish legislation by the end of 2004. Implementation of this directive will mean changes to requirements, and that more products will be subject to separate treatment.

A strategy for hazardous waste will be prepared. The purpose of this strategy will be to identify whether the various regulations related to hazardous waste represent barriers to the best economic and environmental management, and to identify potential initiatives to minimise these barriers. Understanding of how to use the hazardous waste criteria needs to be continually disseminated. New treatment methods for hazardous waste will be developed. Efforts will be made to ensure that criteria for environmental hazards are implemented in Danish regulations.

Impregnated wood containing chromium, copper and arsenic-containing substances will continue to be treated as non-incinerable waste, and landfilled. When better treatment methods have been developed, these types of impregnated wood will be collected separately. Requirements for the management of certain types of impregnated wood will be introduced on the basis of an environmental and cost-benefit assessment.

Mineral wool, as waste, represents a health problem. It is hazardous due to its local irritation and carcinogenic effects. Mineral wool produced after 2000 is less hazardous, as it is considered to only cause local irritation. The potential for recycling mineral wool must be investigated, including the development of recycling methods and of the market for recyclable mineral wool.

District heating pipes can contain ozone layer depleting substances, such as CFC's and HCFC's. Regulations for separate treatment of pre-insulated district heating pipes will be laid down. An investigation will also be carried out into the potential for separate treatment of other waste fractions containing ozone layer depleting substances.

Under new EU regulations, Denmark has to recycle 22.5% of plastic packaging in 2008. Greater quantities of plastic packaging must therefore be collected from the construction sector.

PVC waste will be separated. PVC construction waste contains a large fraction of hard PVC that can currently be recycled. Recyclable hard PVC construction waste will therefore be assigned to recycling. Non-recyclable PVC waste will be landfilled. When suitable treatment methods have been developed, new requirements for special management of such waste will be laid down, if this is considered to be environmentally and cost-effective.

PCB is used in sealing compounds and to seal insulating glass. A project will be initiated to investigate the health impacts associated with the use, renovation or demolition of buildings containing PCB. The project will focus on an evaluation of the PCB contribution from building dust, indoor air and soil close to buildings.

Residues from power plants, waste incineration and soil are widely recycled in building and construction works. Guidelines on the recycling and relocation of soil and residues will be prepared. Statutory Order no. 655 of 27 June 2000 on recycling of residues and soil for building and construction purposes will be revised to also cover soil contaminated with organic compounds.

Tiles represent approx. 5% of building and construction waste. In the longer term, regulations governing the management of tiles will be covered by the Statutory Order on recycling of residues and soil for building and construction purposes.

Under new EU regulations, Denmark has to recycle 15% of wooden packaging and 55% of all packaging waste in 2008. In order to achieve this goal, an analysis will initially be completed of the volume of wooden packaging waste, and potential buyers. Wooden packaging will also be included in the transport packaging agreement, and requirements for the separation of wooden transport packaging will be laid down.

3.5 Landfill sites

In 2001, 1.3 million tonnes waste were landfilled. Over the last 15 years, attempts to reduce the volume of landfilled waste have been successful.

The design and operation of landfill sites must conform to the requirements in the Statutory Order on landfill sites.

As a consequence of Denmark's implementation of the EU Directive on the landfill of waste, the number of landfill sites in Denmark is expected to be further reduced.

Cross-cutting initiatives

The potential to recycle/utilise waste must constantly be investigated so that in the future, waste will only be landfilled when it is environmentally appropriate and responsible to do so.

Requirements will be laid down governing the design and operation of landfill sites and limit values for the leaching characteristics of waste. These will aim to ensure, as far as possible, that the consequences of a failure in the environmental protection systems does not lead to irreversible damage to nature and/or the environment surrounding a landfill site.

As a result of the implementation of the EU Directive on the landfill of waste (including annex harmonisations) the contents of the landfill guidelines from 1997 have become obsolete in a number of areas. The landfill guidelines therefore need to be updated, giving special attention to a description of the future Danish waste characterisation requirements aimed at ensuring "sustainable landfilling".

Training plans, training material and various tests will be prepared with the aim of ensuring that employees at landfill sites can attain the certificates required under the Statutory Order on training [9].

Landfill sites, initiatives

| Cross-cutting | In the future, waste should only be landfilled where it is environmentally

appropriate and responsible to do so

Requirements will be laid down for the design and operation of landfill sites, and criteria and limit values for the leaching characteristics of waste As a result of the implementation of the EU Directive on the landfill of waste (including annex harmonisation) the landfill guidelines from 1997 will be updated Training plans, training materials and various tests will be prepared for employees |

| Seabed sediment | Preparation of a new administration basis for managing seabed sediment

Other possible relevant initiatives |

The Minister for the Environment, together with representatives from Danish Regions, Local Government Denmark (LGDK) and the Association of Danish Ports, is considering a new administration basis for managing seabed sediment. This is expected to be available in autumn 2003 at the earliest.

Further potential relevant initiatives are awaiting the contents of the proposal for a new administration basis.

Aims for 2008

- ensure that consumers have the opportunity to choose products that help prevent waste

- increased information about collection of hazardous waste from households

- 33% recycling of household waste

- 60% incineration of household waste

- 7% landfilling of household waste

3.6 Households

Household waste consists of domestic waste (including paper, glass and food waste collected separately), bulky waste, and garden waste. A small proportion of household waste is hazardous.

From 1995 to 2001, there has been an increase in the volume of household waste. The major part of this increase can be attributed to garden waste in particular. The increase should also be considered in the context of increased purchasing power and private consumption in the nation.

Focus must be given to consumption, and the resulting volumes of waste.

| Cross-cutting | Efforts to communicate information about the municipal schemes will be increased

An information campaign will be run on the link between consumption and waste volumes Information and teaching materials on resource consumption and waste prevention will be prepared for pre-schools, and primary and high schools. |

Cross-cutting initiatives

In order to meet the aims for domestic waste, garden waste and bulky waste, it will be necessary to involve the public in the various collection schemes. This will require increased communication activities within each municipality in order to create the greatest possible awareness of the specific waste collection schemes, including schemes for hazardous waste.

Another purpose of information activities is to increase people's interest in purchasing products that have a lower environmental impact throughout their entire life cycle, and generate as little waste as possible. The Ministry of the Environment will conduct an information campaign on the link between consumption and waste volumes, with specific recommendations regarding, for example, quality/durable products, products made from recycled materials, reusable packaging and packaged goods, etc.

Many consumption and behaviour patterns become established as children. To ensure that future generations are conscious of resource and waste problems, information and teaching materials will be prepared for pre-schools, and primary and secondary schools. This material will highlight the link between increased consumption and environmental problems related to resource consumption and waste generation. Similarly, all children's day-care centres and educational institutions should be encouraged to sort their own waste.

3.6.1 Domestic waste

Aims for 2008

- 20 % recycling of domestic waste

- 80 % incineration

- Recycling of domestic waste can be increased, and in the years ahead, focus will be given to increased separation and collection of plastic and metal packaging, due to our obligations under the EU Packaging Directive.

Domestic waste, initiatives

| Organic domestic waste | The Ministry of the Environment will develop a tool to be used to evaluate

locally the environmentally and economically most appropriate management This will enable municipalities to assess whether two-part collection of the organic component of domestic waste should be locally introduced, and make a decision about this Focus on cheaper collection systems and the development of pre-processing technologies Initiate investigations into central sorting of the combined domestic waste, with the aim of recycling the organic component |

| Plastic packaging | Mandatory schemes for the collection of plastic containers and bottles must be introduced as a consequence of the EU Packaging Directive |

| Metal packaging | Increased recycling of metal packaging as a consequence of the EU Packaging Directive |

A tool will be developed to help municipalities evaluate whether incineration, biogasification or composting of the organic component of domestic waste is best. This will enable municipalities to assess which treatment for organic domestic waste is environmentally and economically most effective and make decisions accordingly.

Previous studies have shown that the two-part collection and pre-treatment of waste is particularly expensive and has a critical impact on whether it is economically viable to recycle organic waste. The aim is therefore to reduce collection costs and develop pre-processing technology. As an alternative, the possibility of sorting the combined domestic waste centrally in order to recycle the organic component is being investigated, taking into account both environmental and working environment factors.

From 2005, municipalities will be required to give people the opportunity to separate the relevant plastic packaging and deliver it for recycling, for example at recycling centres.

Requirements will be laid down for increased collection of iron and metal packaging from households, for example, via recycling centres or under existing bulky waste schemes.

Aims for 2008

- 25 % recycling

- 50 % incineration

- 25 % landfilling

3.6.2 Bulky waste

Recycling of bulky waste can be increased by reorganising or improving existing schemes. In recent years, many municipalities have set up manned recycling centres, often supplemented by collection schemes.

Bulky waste is an area that requires local solutions and where there are advantages in building networks.

Cross-cutting initiatives

The Ministry of the Environment will encourage municipalities to participate in establishing or improving existing re-use schemes for bulky waste. Well-developed schemes to ensure that reusable products do not end up in the waste system should be spread to more municipalities, possibly in cooperation with charities.

Municipalities will also be encouraged to extend the municipal bulky waste schemes to cover many more recyclable waste fractions, so that the volumes collected in the incinerable and non-incinerable fractions can be reduced.

It is not feasible to calculate the environmental and socio-economic effects of alternative forms of treatment for the many hundreds of different products that end up in bulky waste. Municipalities will therefore have to base their evaluations of which types of products should be directed to recycling on the waste indicators for the various material types and on the potential markets for the various fractions.

Municipalities will be encouraged to establish networks for staff at recycling centres and involved in collection schemes for bulky waste, to allow them to share practical experience, including knowledge of potential markets for the many material fractions and products in bulky waste.

The Ministry of the Environment will also encourage building associations and other apartment buildings to establish bulky waste schemes to ensure that re-usable items do not end up in the waste system (exchange centres), and that recyclable waste fractions are separated for recycling.

Waste collection staff and property administrators should be in close contact with residents to inform them about correct separation of their waste, with the particular aim of increasing the re-use and recycling of bulky waste. Municipalities will therefore need to take the initiative to train and instruct janitors, caretakers, waste collection staff and staff at recycling centres, to equip them to give better advice to people about waste separation.

Bulky waste, initiatives

| Cross-cutting | Municipalities will be encouraged to participate in establishing or improving

existing re-use schemes for bulky waste

Municipalities will be encouraged to extend municipal bulky waste schemes to cover many more recyclable waste fractions Municipalities will be encouraged to establish networks for staff at recycling centres, etc. Building associations and other apartment buildings will be encouraged to establish bulky waste schemes for re-usable and recyclable items Municipalities should take the initiative to train and instruct janitors, caretakers, waste collection staff and staff at recycling centres, to equip them to give better advice to people about waste separation. |

| Electrical and electronic products and refrigeration equipment | The EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment must be implemented by the end of 2004, including regulations for the management of refrigeration equipment |

| Impregnated wood | Efforts will be made to ensure that only wood impregnated with chromium, copper, and arsenic-containing substances is treated as waste not suitable for incineration. |

| PVC | New requirements for the management of PVC waste will be prepared |

Electrical and electronic products will be collected separately and managed in a more environmentally sound manner. Requirements for their management were laid down in a Statutory Order issued in 1998. The new EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment has to be implemented in Danish legislation by the end of 2004. Implementation of this directive will mean changes to requirements, and that more products will be subject to separate treatment, including refrigeration equipment. The directive is based on producer responsibility.

Impregnated wood containing chromium, copper and arsenic-containing substances will continue to be treated as waste not suitable for incineration, and landfilled. When better treatment methods have been developed, these types of impregnated wood will be collected separately. Requirements for the management of certain types of impregnated wood will be introduced on the basis of an environmental and cost-benefit assessment.

Efforts will be made to ensure that PVC waste is managed in an environmentally responsible and cost-effective manner. This can be achieved by drafting requirements for the collection and management of PVC waste.

3.6.3 Garden waste

Aims for 2008

- 95% recycling

Municipalities have voluntarily established schemes and facilities for composting garden waste. It is not expected that recycling of garden waste can be increased further [10].

Existing initiatives will be maintained, and no new initiatives are expected in this area.

3.7 Industry

The recycling goal for industrial waste for 2004 has almost been reached, but too much waste is being landfilled. Concerted efforts will therefore be made to reduce the volume of landfilled waste, while maintaining the recycling rate of 65%.

Aims for 2008

- 65% recycling

- maximum 15 % landfilling

- improved collection of hazardous waste

The aim for 2008 is to reduce the volume of landfilled waste to a maximum of 15%. A study has shown that shredder waste and foundry waste account for 27% of industrial waste landfilled in 1997, corresponding to approx. 190,000 tonnes [11].

Other fractions will be separated to increase recycling, if environmental cost-benefit analyses indicate a benefit from doing so. These fractions are described below.

Cross-cutting initiatives

Measures will be initiated to prevent waste. Information on volumes of waste, composition, and potential for recycling will be improved in future preparation of environmental approvals, green accounts, and in the establishment of environmental management in enterprises.

Environmental approvals will be improved in the area of waste management. With the implementation of the IPPC Directive [12] in Statutory Order no. 807 of 25 October 1999, as most recently amended by Statutory Order no. 606 of 15 July 2001, on approval for specially polluting activities, the waste component has been given high priority. Section 13(2), no. 4 of the Statutory Order states that the enterprise must take the necessary steps to avoid waste generation, and where this is not possible, to exploit the potential for recycling and recirculation.

Assessment will be made as to whether increased use of environmental management in enterprises can be best achieved through sector agreements or whether guidelines on conditions for waste reduction need to be prepared for enterprises subject to approval and not requiring approval. These guidelines could also describe BAT's (Best Available Techniques) to help reduce waste, etc., for a number of waste-intensive enterprises, and the significance of BAT's in relation to the maximum waste volumes.

The existing waste analysis model will be refined so that it can also be used in large enterprises. The model can identify fractions for which internal recycling of the enterprise's waste can be increased.

Product wastage at the consumer due to inappropriate packaging that is impossible or difficult to completely empty could be significantly reduced if packaging designers and manufacturers developed packaging that it was possible to empty. Packaging manufacturers and producers who fill packaging will therefore be encouraged to develop and use better packaging that reduces wastage.

Based on both an environmental and economic assessment, efforts should be made to ensure that large plastic containers (over 20 litres) from industrial enterprises are re-used. It is expected that regulations will be implemented, requiring large containers to be separated for re-use or recycling.

In general, too much industrial waste is landfilled. Specific initiatives will be carried out, targeting individual fractions and sectors.

Industry, initiatives

| Cross-cutting | Measures will be initiated to prevent waste

Information on volumes of waste, composition, and potential for recycling will be improved Environmental approvals will be improved in the area of waste management as a result of implementation of the IPPC Directive [13] The existing waste analysis model will be refined so that it can also be used in large enterprises Product wastage at the consumer due to inappropriate packaging that is impossible or difficult to completely empty can be significantly reduced It is expected that regulations will be implemented, requiring large plastic containers to be separated for re-use or recycling Guidelines on conditions for waste reduction for enterprises subject to approval and not requiring approval will be prepared, or sector agreements to this end will be established Specific initiatives will be carried out, targeting individual fractions and sectors to reduce landfilling |

| Animal waste | Investigate the possibility of supplying animal waste to biogasification plants,

especially abattoir waste

Investigate the possibility of recovering phosphor from slag from incinerated meat-and-bone meal |

| Vehicle waste | Requirements will be laid down for increased recycling of plastic components

Recycling of waste from end-of-life vehicles will be increased as a result of an EU directive |

| Electrical and electronic products | The EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment must be implemented

by the end of 2004

Better resource utilisation through the development of new technologies for reprocessing products. |

| Tyres | Information campaign to limit damage during fitting, and promote the sale of retreaded tyres |

| Hazardous waste | A strategy for hazardous waste will be prepared

The criteria for environmental hazards will be implemented New treatment methods for hazardous waste fractions will be developed Information on hazardous waste regulations will be communicated |

| Refrigeration equipment | Regulations for the management of refrigeration equipment will be included in a revised Statutory Order on management of waste electrical and electronic equipment |

| Plastic | A greater percentage of plastic film transport packaging must be recycled under the EU Packaging Directive |

| Metal | Increased recycling of metal packaging as a consequence of the EU Packaging Directive |

| Wooden packaging | Under the Packaging Directive, 15% of wooden packaging must be recycled in 2008 |

| Impregnated wood | Impregnated wood containing chromium, copper and arsenic-containing substances will continue to be treated as non- incinerable waste, and landfilled. Once better treatment methods have been developed, impregnated wood will be collected separately, if this is assessed to be environmentally and cost-effective |

| Glass | Initiation of development activities aimed at developing alternative recycling processes for glass fragments |

| PVC | The volumes of PVC marketed and potential waste volumes will be determined

Draft requirements for the management of PVC waste will be prepared Criteria for exemption from the PVC tax will be prepared Chemical treatment plants will be exempted from waste tax to promote recycling of new technologies PVC products that end up in waste incineration plants will be replaced Efforts will be made to ensure that PVC products containing lead and cadmium are separated, either for chemical treatment or landfilling |

| Shredder waste | Development of new treatment methods for extracting heavy metals |

| Foundry waste | The development of recycling methods will be promoted |

The EU Animal By-Products Regulation, administered by the Danish Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, has led the Ministry of the Environment to issue new regulations for the recycling and disposal of animal waste, including industrial kitchen waste, in the Statutory Order on sludge. The aim of these regulations is to ensure optimal treatment of animal waste, based on environmental considerations. Investigations will be carried out into the possibility of recycling increased volumes of animal waste for agricultural purposes through biogasification. Trials will be carried out on the recovery of phosphor from slag from incinerated meat-and-bone meal.

Requirements for increased recycling of plastic components resulting from an EU directive will be laid down through an amendment to the Statutory Order on management of waste in the form of motor vehicles and derived waste fractions. Initiatives supporting the development of new separation technologies aimed at recycling plastic and exploiting other organic fractions will be promoted as far as possible. Analyses of treatment technologies have been carried out. This work will continue with the aim of establishing plant to exploit shredder waste derived from end-of-life vehicles and a number of other composite products.

Electrical and electronic products will be collected separately and managed in a more environmentally sound manner. Requirements for their management were laid down in a Statutory Order issued in 1998. The new EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment must be implemented in Danish legislation by the end of 2004. Implementation of this directive will mean changes to requirements, and that more products will be subject to separate treatment. The directive is based on producer responsibility.

Regulations on the waste treatment of refrigeration equipment will be incorporated in a revised Statutory Order on management of waste electrical and electronic equipment, expected to be issued in 2004.

Further to the action plan for environmentally aware public procurement officers, guidelines have been prepared for public procurement officers on a number of items of electronic office equipment, and eco-labelling criteria will be prepared for several products. The development of new technologies for reprocessing electrical and electronic equipment will be evaluated regularly. Amendments to regulations to promote the use of best available technology will be made as the need arises.

Under the agreement with the Danish Tyre Trade Environmental Foundation, information campaigns will be conducted, aimed at minimising the volume of waste and promoting the use of retreaded tyres.

A strategy for hazardous waste will be prepared. The purpose of this strategy will be to identify whether the various regulations related to hazardous waste represent barriers to the best economic and environmental management, and to identify potential initiatives to minimise these barriers. Understanding of how to use the hazardous waste criteria needs to be continually disseminated. New treatment methods for hazardous waste will be developed. Efforts will be made to ensure that criteria for environmental hazards are implemented in Danish regulations.

Separation of plastic film transport packaging from industry must be increased under the EU Packaging Directive. Municipalities will have to give priority to monitoring that plastic transport packaging is collected for recycling. Waste producers will have to participate more actively in the organisation of effective schemes. It needs to be easier for sector associations that represent waste producers/retail chains to establish nationwide collection schemes. The legislative changes necessary to support this will be investigated with the aim of amending the legislation in 2004, so that the new schemes can function from 2005. Increased focus will also be given to enterprises that produce large volumes of plastic film waste. Finally, it may be necessary to extend the requirements on collection to cover smaller enterprises.

Separation of other plastic packaging from industry must also be increased. The potential for recycling and re-using plastic containers from trade and industry has been investigated. Environmental and economic factors will also be investigated. When the project has been completed in the middle of 2003, a decision will be made on which types of packaging need to be separated.

Iron and metal packaging must be referred to recycling.

Impregnated wood containing chromium, copper and arsenic-containing substances will continue to be treated as waste not suitable for incineration, and landfilled. When a plant has been established, these types of impregnated wood will be collected separately. Requirements for the management of certain types of impregnated wood will be introduced on the basis of an environmental and cost-benefit assessment.

Under new EU regulations, Denmark must recycle 15% of wooden packaging and 55% of all packaging waste in 2008. In order to achieve this goal, an analysis will initially be completed of the volume of wooden packaging waste, and potential buyers. Wooden packaging will also be included in the transport packaging agreement, and requirements for the separation of wooden transport packaging will be laid down.

A project was initiated in 2002 to find alternative uses for glass packaging. This project will determine volumes and evaluate the potential for using glass in cement, tiles and road construction. There will be a need for further development and trials of other methods for alternative uses for glass.

A work group will be set up to determine the marketed volumes of PVC and propose a model for calculating the expected volume of waste. The volume of waste will be estimated through to 2020.

Efforts will be made to ensure that PVC waste is managed in an environmental and cost-effective manner. This can be achieved by drawing up requirements for the collection and management of PVC waste, and providing tax exemption for products that are managed in an environmentally responsible manner. Efforts will be made when drafting future regulations for the management of PVC waste to ensure that products containing lead and cadmium are separated, either for chemical treatment or landfilling. If exemptions are granted for the sale of products containing lead, guidelines will be prepared on how recycling of the regenerated PVC material containing lead can be carried out. In order to promote the use of new technology for processing PVC waste, an amendment to the Act on taxes on waste and raw materials will be sought, such that new plants are exempted from paying waste tax.

It is not possible to keep waste incineration plants completely free of PVC waste. The Environmental Protection Agency has evaluated alternative products for soft PVC building products. Other areas will be continually evaluated to examine the potential for promoting the use of alternatives to the products that end up at waste incineration plants.

It is expected that a decision can be made during 2003-2004 on which treatment should be used for shredder waste. Initiatives that monitor and support the development of better treatment methods that can utilise the resources contained in shredder waste will be promoted as much as possible. Once the treatment technique is ready, regulations for the future management of shredder waste will be prepared, based on a cost-benefit analysis.

It is currently technically possible for a large proportion of waste from foundries to be recycled. Efforts will be made to ensure that all foundries in Denmark work towards recycling this waste, if this is found to be environmentally and cost-effective.

3.8 Institutions, trade and offices

Aims for 2008

- 50 % recycling

- 45 % incineration

- 5 % landfilling

Recycling of waste from institutions, trade and offices [14] is far below the goal of 50% for 2004. Over the next few years, focus will therefore be given to separation of a number of waste fractions for recycling or special treatment.

The aim for 2008 is to achieve a recycling rate of 50%. This will primarily be achieved through source separation of a number of fractions for recycling. A number of these initiatives are aimed at ensuring compliance with targets in the relevant EU directives. Other initiatives will only be carried out if environmental cost-benefit analyses show them to be beneficial.

Cross-cutting initiatives

The existing waste analysis model will be refined so that it can also be used by service enterprises. The model can identify fractions for which internal recycling of the enterprise's waste can be increased.

The trade and repair sectors need to be encouraged to extend, improve and optimise the use of returnable transport packaging and make greater use of reusable transport packaging in general.

The Danish Environmental Council for Cleaner Products appointed a Retail Trade Panel in 2002. The aim of the panel is to generate activities to change attitudes and behaviour, with the aim of reducing the total environmental impact from the retail trade. The panel also aims to promote the range of and market for cleaner products in the area of convenience goods. In the area of waste management, the panel will initiate activities relating to organic waste, packaging waste, shop personnel training and packaging systems.

Institutions, trade and offices, initiatives

| Cross-cutting | The existing waste analysis model will be refined so that it can also be used by service enterprises The trade and repair sectors will be encouraged to make greater use of reusable transport packaging The Retail Trade Panel will initiate activities relating to organic waste, packaging waste, shop personnel training and packaging systems |

| Animal waste (food waste from industrial kitchens and organic waste from the retail trade) | The best way of managing organic waste from the trade of convenience goods and ways of making it easier for retail chains to organise nationwide collection of organic waste need to be identified |

| Vehicle waste | Requirements will be laid down for increased recycling of plastic components Recycling of waste from end-of-life vehicles will be increased in accordance with an EU directive |